‘Your Mother Is Unwell’: Grave Talks of Kashmir

Umar Hayat Hussain has worked with Kashmir Life, Kashmir Impulse,…

Some Kashmiris who lost their loved ones to the strife situation have picked up an uncanny routine with time to bring some solace in their battered lives.

The four visitors that defied the graveyard silence with their spoken sorrows made a summer day even more restive for the cemetery regulars. They came and whispered prayers before settling down with their uncanny speaking sessions. Among them were an aged father, a young son and a withered widow.

But first, came a burka-clad woman.

She headed towards a fading grave inside a tombstone-dotted landscape at the strife-scarred corner of downtown Srinagar. She put down her bag and embraced the grave as if greeting someone in person. The emotional embrace lasted till she ran out of her dirges.

“This is not normal,” says Mushtaq Bhat, a hunched elder frequenting Srinagar’s Eidgah for Fatiha.

“Kashmiris would normally visit graveyards to offer silent prayers for the departed souls or cry in their longing, but over the years, as I’m witnessing it, many people tormented by the situation are arriving to talk to their martyred loved ones.”

Support Our Journalism

You are reading this because you value quality and serious journalism.

But, serious journalism needs serious support. We need readers like you to support us and pay for making quality and independent journalism more vibrant.

The same grieving routine is now binding the mother with the graveyard.

The cemetery is tucked in the tightly crammed timber-brick houses. The graves are neatly laid out in rows on the carpeted green grass. Roses and irises bloom among the gravestones. The names scripted on the epitaph are fading away due to time’s whiplash and vagaries of weather. Tombstones are topped with garlands of withered and plastic flowers.

Since its war-footing inception some thirty years ago, the cemetery has been twice enlarged—leading to the grave to be doubled, and then quadrupled—after running out of its initial 120×120-feet space.

Graves are not dug at Eidgah, but rather soil is raised around rock plinths. Even today, locals say, more than 10 graves have been kept ready to hem in the fresh ones.

The mother in her mid-fifties got up and opened her bag. She took out a fistful of grains and petals and spread it carefully over her son’s gravestone.

Her cries were competing with boisterous calls of children playing cricket in an adjacent park. It was a strange amalgam of the two voices — one coming from a woman crying her heart out for her slain son, and the other materialized from the intensity of a cricket match. It seemed as if Eidgah was a no-man’s land where ambits of past and present get glued together.

The grave conversations, however, don’t surprise the locals anymore. They’ve been witnessing the family members of the departed visiting the cemetery for unburdening their hearts for a long now.

Some of them even say that the armed upheaval of the late eighties and the subsequent military offensive changed the identity of the 400-Kanal Eidgah, gifted to Kashmir some 600 years ago for offering Eid prayers by Shah-e-Hamdan’s son, Hazrat Mir Muhammad Hamdani (RA).

“Young Kashmiri women would once perform rouf (folk dance) to the song: “Eid aaye rase rase, Eidgah waes waey” (Steadily, steadily, Eid has come; let’s go to Eidgah),” says Abdul Rehman, a local resident. “But who knew that one day some of them would be singing dirges to their slain sons and spouses here!”

As the militant-military clashes dominated the scene during the 90s, myriad parks were metamorphosed into burial grounds — where thousands of Kashmiris were buried. One of them was Eidgah, where the mother’s son among others was taken as a ‘conflict casualty’.

To eavesdrop on the mother’s monologue with her slain son, I carefully took the walk around and started offering prayers for a “Shaheed”. My legs shortly froze with the sound of the spoken sorrow.

“My body is giving up on me now, son,” I heard her saying loud enough. “Even medicines aren’t helping now. Your senile father is struggling for work again … We miss you by our side. Wish you could have been here, with us …”

Eidgah’s Martyrs’ graveyard is a grim outhouse of many such talks — making the whole ambience poignant for visitors and residents.

But before these grave talks, people would mainly assemble in Eidgah to pray for forgiveness—especially during calamities.

“It’s the same ground where holy relics were exhibited to the large gathering after prayers,” said Zareef A. Zareef, Kashmir’s noted chronicler.

People would fight to secure their front-row praying spots for having a clear glimpse of the relics. In worse cases, such clashes would even lead to the shedding of blood which itself was considered to be a good omen.

“Before 1947, the Dogra Maharaja used to enquire from his courtiers: ‘Khoon padaye, naful huvuya’ (Has blood fallen, special prayers performed),” Zareef says.

“Behind his concern was an unshakable belief of Kashmiris that blood falling on the sacred ground meant prayers accepted by Almighty!”

But after the same praying ground got mutated into martyrs’ graveyard with the arrival of the blood-dripping bodies during the nineties, this crown concern resurfaced in certain Kashmir conversations.

Once done with her dirges, the mother got up and walked away. The competing pitch created by her cries and the screaming sports at once turned one-sided. The game won, as the invading graveyard silence hushed the grief for the day.

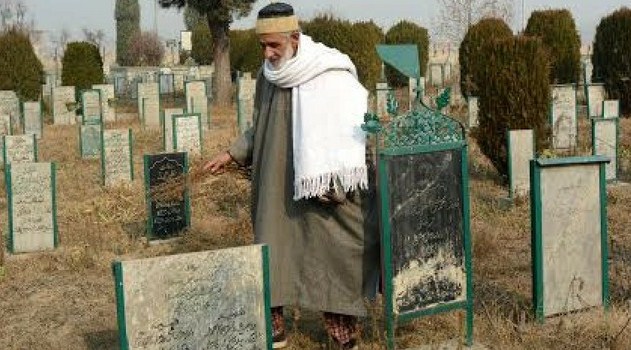

And soon came a septuagenarian wearing grey stubble, sad eyes, white skullcap, and well-ironed Khan Dress. He stood before the gravestone of his son.

“Gobra,” he started his soliloquy, “Mouj chaye bemaar (Your mother is unwell). Tell Allah to give her Shifa. Inshallah, we will meet soon.”

The discernable talk struggled for rhythm before the father sat down to convey his longing in depth and detail. “My heart was getting restless, thought to visit you…”

Outside the cemetery, a shopkeeper termed these grave talks as a sign of brutalization.

“Our tragedy lies in our elusive wait for closure,” the bearded man said with sage’s stillness.

“For years now, these visitors are living with their trauma. I’ve seen families coming from different parts of the valley just to talk and cry their hearts out here. Such distressed visits are quite common in shrines, where people cry and seek divine intervention in their matters.”

In the afternoon of that summer day in 2021, came another person. He headed towards a grave placed in the middle of the cemetery.

For a while, the young man, apparently in his early thirties, stood quiet, before he started talking.

“Daddy, Khuda soab gous sahal karun (Father, may Allah ease our hardships). Nothing seems to work these days. Life is getting demanding and there seems no help…”

The young man as it turned out was detailing his distress to his “Shaheed” father killed in a “cross-firing” in the early nineties.

While the young man was pouring his heart out to his silent father, the bearded shopkeeper outside talked about a young woman who would visit the cemetery once in a week.

“She isn’t turning up now,” the elder says. “Most of these grave visitors often obscure from the scene, as if consumed by their own grief. Sadly, their grave talks end when they reunite with their loved ones in the grave!”

To voice the same grief, a widow came whispering dirges at the twilight of that blistering day.

Shedding some light on her sorrow, Saleem, a local resident, said she has been visiting her “young groom” for years now.

“She comes with fresh petals, spreads it over the grave and starts talking,” he said. “This way the woman has been unburdening her heart since the day she became a widow from a new bride!”

Mountain Ink is now on Telegram. Subscribe here.

Become Our Ally

To help us strengthen the tradition of quality reading and writing, we need allies like YOU. Subscribe to us.

Umar Hayat Hussain has worked with Kashmir Life, Kashmir Impulse, Kashmir Times, Kashmir Reader, among other publications. He is currently an editorial intern at the Mountain Ink.