‘There’re Traces of Kashmir All Over Central Asia’: Baker Recalls on Jhelum Bund

Arif Nazir is a Staff Writer at the Mountain Ink.

A living witness to Kashmir’s tumultuous history, a baker from Old Srinagar is a stark signpost of Kashmir’s Central Asian connection.

Dawn of a searing summer day makes Kashmir’s Aali Kadal look entrancing, with its old-world charm and waning architectural landscape. Some traditional washermen shouldering bundled shawls show up as early birds. The sun rising behind a distant hillock and rusty residential roofs light up the Bund specked with syncretic symbols. Mosques and temples shimmer in coexistence, so do Hydaspes — on whose faraway banks legendary Alexander fought his last battle.

Under the shade of this captivating life, Ghulam Nabi Kitass has been carrying out his untiring routine from the last five decades. He has seen it all— the classic ‘Sher-Bakra’ tussles, the rise of turncoats, the sneaking rebels of yore, the mortal machines, the boat ambush sealing the fate of a top gun, and the bridge where once romance thrived, for Cupids of Kashmir were yet to pick a grave routine.

Kitass starts early, soon after a multitude of muezzins drive out the darkness with the announcement of a new day in Kashmir.

He pulls up shutter over his 50-year-old grocery shop, with ‘Bismillah’. The creaking sound of his shop-shutter reverberates in a still-sleepy city pocket nestled on Jhelum Bund.

While he steps in and settles down at his small resting place, the septuagenarian down his faded memory-lane travels a nostalgic journey to trace the roots of his Central Asian ethnicity.

Support Our Journalism

You are reading this because you value quality and serious journalism.

But, serious journalism needs serious support. We need readers like you to support us and pay for making quality and independent journalism more vibrant.

Kitass’s forefathers had moved to Kashmir some three hundred years back from Central Asia. He grew up hearing to the Silk Route odyssey as fascinating folklore.

“My father, who was a baker by profession, used to write and receive letters from his relatives in Tashkent,” Kitass speaks of a faded memory from his childhood. “But as I grew up, those communications stopped. Post-1947 scenario, followed by the Indo-China War of 1962 and ’67, changed everything.”

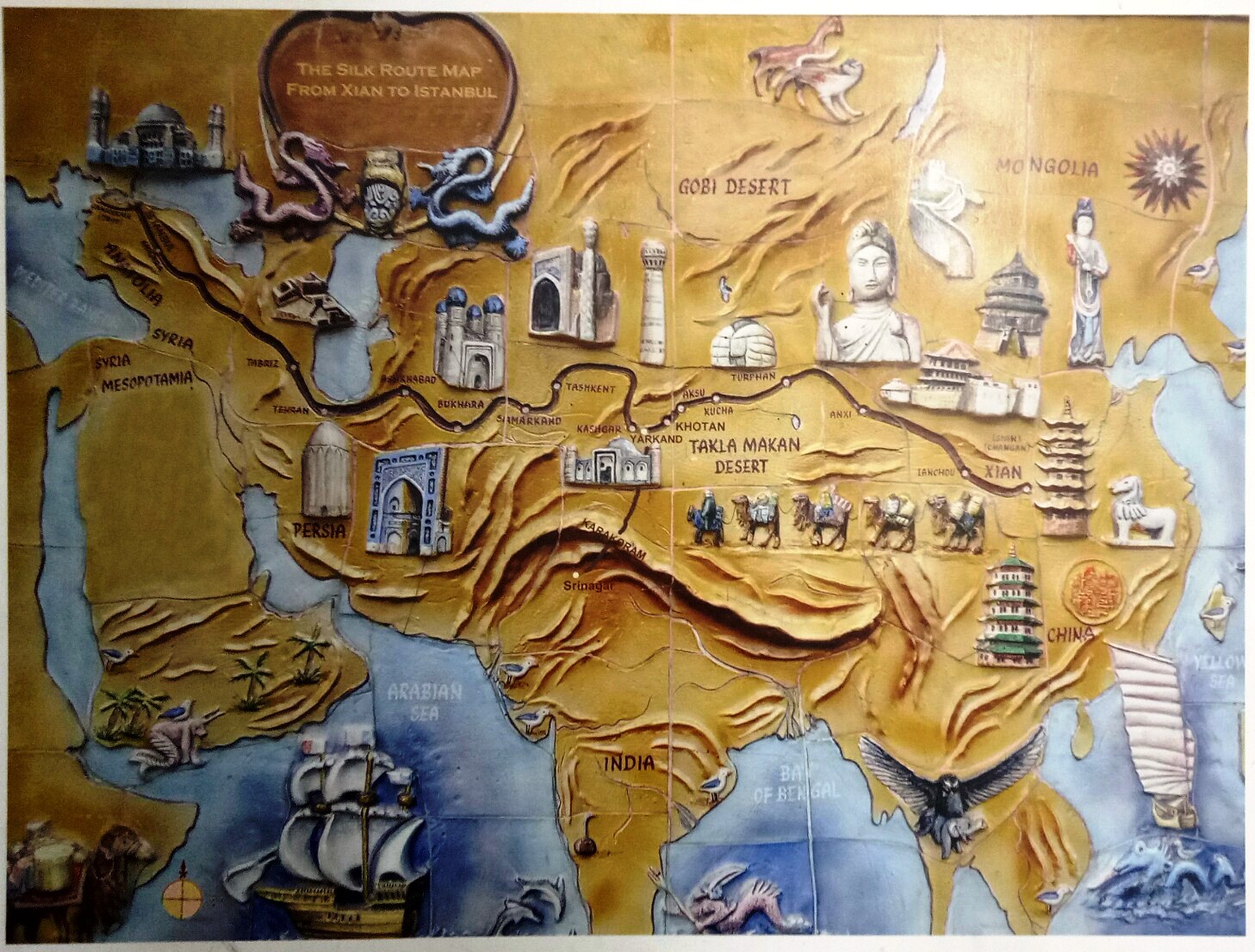

Kashmir back then was an active trade zone and cultural melting pot, but the traditional routes connecting Kashmir with fabled Silk Route got blocked due to the new cartographic lines drawn in what was to become the world’s oldest conflict zone.

But before Kashmir would be solely linked with the fair-weather Srinagar-Jammu highway, Kitass had interacted with those travel-weary traders who would traverse Silk Route to reach Srinagar.

Among other things, he remembers his childhood gestures and giggles with those Central Asian merchants.

“I have a blurred image of those faces in my mind that would stop by to greet my late father,” says Kitass. Those travellers from Tibet, Uzbekistan and other parts of Central Asia would make their final stop at Yarkand Sarai, or Travellers Inn, at Srinagar’s Safa Kadal.

“I grew up hearing stories about erstwhile Kashmir’s ties with the trade hubs of Central Asia from my late father and the traders riding on horses all the way from Tashkent to Srinagar,” Kitass continues.

His face beams with joy as he speaks of his father’s attention-grabbing rides on a horse bought from a traveller from his ancestral homeland.

“The whole locality, for almost a week, ran after my father’s superior and striking horse,” he remembers what his elders in the neighbourhood remembered of the day.

But soon after his father’s demise, poverty came knocking on his door. “When my father passed away, I didn’t know what to do, as I wasn’t a baker like him.”

With his joys disappearing like a beautiful dream, Kitass, now sporting a snow-white beard, had to spend his youth in struggle.

Getting married, having kids, and stepping up to the family responsibilities became his priorities in life. For a living, he started a small grocery shop. It gave him a hard time.

Going through a rough patch, he sensed a spiritual void within. He visited godmen to find some solace, some solution.

During that struggling phase, one of his three sons became unwell. “Nothing worked,” he recalls, “until I visited my peer. It just took three taps from the godman on my son’s back to make him healthy again.”

The event would shape up his profound platonic perceptions about life. After his son’s ailment, he began frequenting the godman for driving out destitution from his life.

“Babb, setha gurbatt chem. Kehn dua kartam (I’m down with poverty. Pray for me),” Kitass had asked the godman.

The reply came that he should resume his late father’s baker shop, as soon as possible.

For him, it was a job that needed some small investment at that time, which he couldn’t afford.

“Days and nights kept passing like this and nothing was helping me out,” Kitass continues with a sign of hope shining on his radiant face, as if, it’s happening now.

The wait ended, when his sister-in-law and her son showed up with an amount and interest to resume the baker shop.

Soon the cold tandoor was reignited, and everything out of it “tasted as sweet as honey”, Kitass recalls.

A swarm of early-risers were back for fresh bread from his father’s restored shop. “It all happened out of nowhere,” he says. “I hadn’t ever aimed or dreamed of anything like that.”

Today, his baker shop which he restarted on his Peer’s instruction has become a brand name, not only in Srinagar, but throughout the valley, as ‘Janta Bakery’.

While his sons are taking care of his bakery business, grateful Kitass is still devoted to his grocery shop.

“I’ve always been attached to godmen and travelled miles and distances to reach out to their company,” he says.

With time, his spiritual journey not only sent him to perform three Hajj pilgrimages and fourteen Umrah trips, but also on different expeditions.

Kitass travelled to cities of Syria and Iraq—well before the war would tear them asunder—apart from Iran, Damascus, Tajikistan, and many other countries.

“What fascinated me during those visits is that there’re traces of Kashmir all over Central Asia in the form of culture, traditions, beliefs, rituals, arts and the way of living,” says Kitass, who’s sure of reaching out to his ancestral-homeland that he has heard of being somewhere between Tajikistan and Tashkent.

Once done narrating personal history, the baker walks up to Jhelum Bund, where he often stands like a lost traveller longing for his lost tribe. A small distance away, Travellers Inn stands akin to a pale shadow of its glorious past. What used to be a bustling place has now become a silent shelter of some trapped travellers’ progeny.

All this makes the baker sad.

“If only they hadn’t cut our route,” the old man mused at the ghats of Jhelum, “life in this part of the world would’ve been different.”

To help us strengthen the tradition of quality reading and writing, we need allies like YOU. Subscribe to us.

Mountain Ink is now on Telegram. Subscribe here.

Become Our Ally

To help us strengthen the tradition of quality reading and writing, we need allies like YOU. Subscribe to us.