The Professor’s Perspective and Protagonist

Hirra Sultan is a Srinagar-based writer. Her works have appeared…

Despite its selective take on Abdullah, the book makes a good, informative read and creates a good base for someone who wants to delve into the history of the place and unearth the truth.

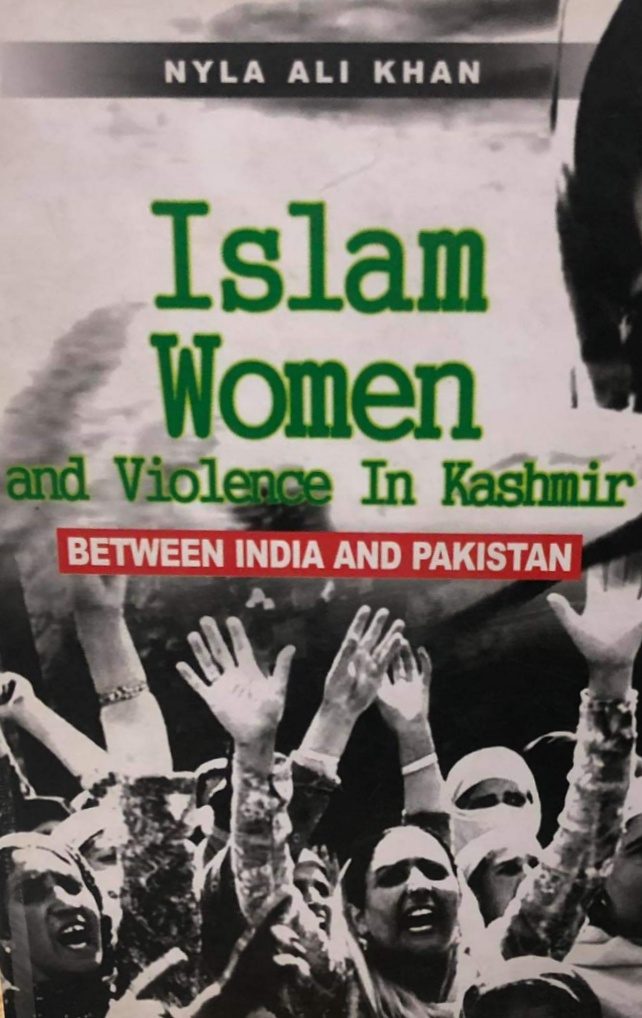

Nyla Ali Khan’s Islam, Women and Violence in Kashmir: Between India and Pakistan is primarily a non-fictional recollection of memories and history of Kashmir from the perspective of the author.

Even though the book was first published in 2008, it still remains relevant 12 years later.

India and Pakistan have been duly portrayed and discussed about along with their role in the current situation of Jammu and Kashmir.

The Kashmir before the partition of the Indian Subcontinent is discussed in depth, giving a good insight into what it was and what it is now.

This portrayal somewhere justifies the demands for Right to Self Determination as promised by India’s first Prime Minister, Jawahar Lal Nehru in United Nations in 1948.

Support Our Journalism

You are reading this because you value quality and serious journalism.

But, serious journalism needs serious support. We need readers like you to support us and pay for making quality and independent journalism more vibrant.

However, there’s clearly no connection of the title of the book to its content. They’re disjointed. Even when it depicts the history well, there’s no Islam, a handful of women and some violence in the book.

Women are to be looked for, with a candle in hand, to be found. Maybe, a chapter is all there in the name of women. Violence has a little more space as Kashmir and violence have become inseparable.

From the perspective of a novice, it is a beautifully done compilation. The illustrations, narrative, description takes you to the scene of action. One can practically find the history repeating itself in front of his eyes.

The only strange fact is that despite belonging to the non-fiction category, the book seemed to have a protagonist: Sheikh Abdullah.

Abdullah’s life is explained beautifully. Beautifully because his mistakes are written about subtly, like admitting there were wrong decisions taken yet keeping his image clear. Like nothing was his absolute fault. It was the fault of fate, or India and more often Nehru but never Abdullah himself.

Reading the book makes it clear why he was titled “Sher-e-Kashmir”. His work in various social sectors is talked about. Yet, his demise from the hearts of people and causes thereof are also there — just subtler than his achievements, making sure his whites remain spotless.

The author is trying to give Abdullah a little cleaner image than he enjoys in Kashmir — especially after his death and post-1989, when the valley witnessed armed uprising against the status quo endorsed and sanctioned by Abdullah itself after returning to the throne as a chief minister.

Any sensible reader might wonder after reading the book: is she trying to restore the “tallest leader’s” lost sheen in the strife society? Or is it that the book is truth and people have doubts because they have heard, seen and experienced otherwise?

But as Abdullah’s granddaughter, Nyla Ali Khan—a Visiting Professor at Rose State College—is only trying to bring forth the lived experiences, interactions and personal readings.

Having pursued postdoctorate in postcolonial literature and a PhD in the field of literature, this book perfectly fits her biography. Maybe somewhere her depiction of Abdullah is justified. That is what any family member would do for his/her family. There is also this possibility that, because this all was happening in her own family, this is how it looked to the Abdullahs. All of what was happening then.

Even though the book has elaborately discussed the history of Kashmir, it somehow missed the exodus of Muslims from Jammu; being forcibly sent to Pakistan and being killed before reaching anywhere.

Another thing is, the gradual loss of Kashmir’s autonomy had been accredited to Nehru. He has been made the defaulter and hence a reason for Kashmir conundrum.

In all of this, Pakistan had a crucial role that has not been downplayed. The instrument of Accession, as signed by Maharaja Hari Singh and Nehru, has also been included at the end of the book which clearly states that the accession is subject to a plebiscite that will be held once the ground situation stabilises.

Yet, under what circumstances or for what reasons Abdullah signed the Indira-Abdullah Accord of 1975 and accepted the eroded autonomous status of Kashmir have not been discussed.

Even though signing that Accord remains the major cause of troubles Kashmir faces today, the grandpa has been given a clean chit.

This is where, it seems, the blood has shown its true colours.

Also, the only role of women has been written in the form of the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP), Dukhtaran Milat (DM), and a women combat group.

That is disappointing because by being mentioned in the title one expects the topic to be explored. Even in everyday lives, when women sit home, they are contributing to the struggle, to the history of Kashmir. This aspect has been overlooked altogether.

A woman crying over the body of her martyred husband or a mother holding her son’s picture in hand, waiting at a military installation has an equal contribution to the history and struggle of Kashmir. But Dr Nyla failed to explore that aspect of the conflict.

The good thing about the book is that it raises some important questions by the end, like why certain things happened in a particular way, the causes of an incident and such.

The notion that if certain things had been different, would we actually be free today? Or is this thought a mere fantasy and we were always meant to live and suffer our condemned fate?

Despite its selective take on Abdullah, the book makes a good, informative read and creates a good base for someone who wants to delve into the history of the place and unearth the truth.

(This Review appeared in the January 2021 print issue of the Mountain Ink.)

To help us strengthen the tradition of quality reading and writing, we need allies like YOU. Subscribe to us.

Mountain Ink is now on Telegram. Subscribe here.

Become Our Ally

To help us strengthen the tradition of quality reading and writing, we need allies like YOU. Subscribe to us.

Hirra Sultan is a Srinagar-based writer. Her works have appeared in many regional publications including The Indus Post, The Counsellor Magazine, Kashmir Observer, among others.