Blast and Brouhaha In Indian Coffee House

Muhammad Nadeem is a reader and writes about what he…

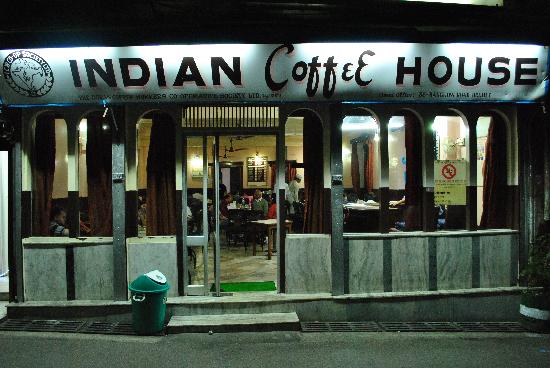

Confused as the ‘house of comrades’ where endless discussions on Marx and Lenin during the Cold War era would spread intellectual airs in Srinagar, a buzzing hangout lost its relevance and place thirty years ago. Even as the coffee-makers have multiplied since then, that classic coffee has stayed a sentimental sip for many.

When a detonation made a deafening noise inside Indian Coffee House in the late eighties, a red brigade hailed as “intellectuals” could see the long-feared conflict finally rearing its explosive head in the serene valley.

As ‘mind-readers’ and ‘pulse-keepers’ of changing times, they were long predicting guerrilla warfare in the backdrop of shifting sands in Islamabad’s strategic depth where legendary warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar was throwing his weight behind the mujahedeen of mountains.

That bathroom blast inside the Coffee House came as a strategic strike when the city comrades were witnessing the burial of “their” soviet soldiers in the “graveyard of empire” at the hands of the turban tribe.

And when one of the coffee shop regulars confused Gwalior with guerrillas, it would evoke sullen tempers than a hearty laughter.

Srinagar was changing, so was the mood inside the faded café run from an imperial building of the iconic Residency Road.

Support Our Journalism

You are reading this because you value quality and serious journalism.

But, serious journalism needs serious support. We need readers like you to support us and pay for making quality and independent journalism more vibrant.

“That deafening detonation did send a message across that the powder-keg valley has finally blown in armed upheaval for their righteous rights,” a former rebel, now strolling as a sundered man around the cafe turned garment shop, says.

“Whosoever did it, the rationale behind the blast was to strike the heart of the intellectual capital filled with news.”

Earlier, after the rigged polls of 1987 and mass detention of polling agents including the incarcerated chief of proscribed JKLF, Yasin Malik, when the similar blasts shook Srinagar, the coffee house would turn dismal over the war forecasts.

But when the explosion came from inside, Arvind Gigoo writes in his Days of Parting, the café ambience at once turned full of conspiracy theories and speculations.

While some said the blast was the work of Pakistan, others blamed Indian intelligence agencies, Gigoo, capturing the militant mood of 1989 inside the Coffee House, writes.

Even the role of the CIA and KGB was suspected.

“Highly imaginative theories were propounded. India, Pakistan, US, USSR, etc. were discussed,” Gigoo recalls. “Pandits said that the ‘Indian army is here to protect us and Kashmir.’ Others laughed at this bomb blast of ‘no significance.’ I was among the laughers.”

But not many were laughing after a ruthless offensive started in Kashmir against the massive upheaval.

Gigoo and his tribe shortly abandoned their home in the horror-struck ecosystem unleashed after Jagmohan returned to Raj Bhavan as the second-time governor.

As Home Minister of India, Mufti Sayeed’s best bet, he had come as “nurse orderly” and ended up presiding over the multiple massacres in Kashmir in his less than five-month governorship.

And soon, among many iconic buildings, Indian Coffee House became a ghost house. The explosive strife would reverberate unabated in the region for the next thirty years.

But for years, the coffee comrades would make rounds of “their lost nucleus” in Srinagar and its tragic end, even as it would mutate into bakery and garment shops.

On the heels of that blast, the ‘Samanbal’ for Kashmiri literati became deserted after a certain militant group would pull down shutters over the “evil” shows and hangouts in Kashmir.

“Regular threats and its Indian identity led to the Coffee House’s demise,” Zareef A. Zareef, a poet and the café regular, says.

Back then, as the Azadi AK-47 surfaced, almost every Indian office was closed in the valley.

“And since it wasn’t an indigenous Kashmiri idea, the Coffee House culminated around 1990,” Zareef laments.

But before its fall, a motley group of people would frequent it — some for leisurely outings, some for artistic reasons, and some for secret policing.

Among others, the coffee house, earlier shifted from Bund to Residency Road, was also frequented by the then ruling party National Conference’s members and musclemen.

“The plough party’s stealthy rank-holders would play prying eyes inside that café,” Zareef recalls. “They kept eye on dissenters.”

Many a times, the party vigilantes would roam around, threatening writers who were considered potential threats to the party’s manoeuvre, the poet, who frequented the café for improving his radio skills, says.

Apart from the party regulars and irregulars, the guest appearances of who’s who in town would make it some kind of an intriguing space in Srinagar.

When National Conference patron Dr Farooq Abdullah once showed up in the café with his cabal, he lived up to his mercurial nature.

“Then Abdullah would freely roam around in Srinagar,” says Sidiq Ali, a septuagenarian man who spent his youth in the coffee house.

“So, one day, when he arrived, he yelled at a travel agent from Srinagar’s Rainawari: ‘How are you, roll number 7?’ That man was his batchmate and that’s how people would suddenly bump into each other in that café.”

Sipping coffee with their ilk, playwrights like Ali Mohammad Lone would conceive plots for some of his popular radio plays inside the Coffee House itself.

Apart from Lone, Bansi Nirdosh, Hardeep Bharti, Akhtar Mohideen and others, the Coffee House had its own ‘Shama’aye Mehfil’—Shameem Ahmad Shameem, the ex-parliamentarian and editor of “Aina”.

“Shameem would always take the ambience upon himself and add flavour to all discussions,” Zareef fondly recalls.

“One needed not to be a person of fame to learn from brilliant minds there. Even without a book in hand, we would learn about history orally. It was the easiest going hub of intellectual vigour which turned me into a voracious reader and a writer that I am today. I don’t hesitate to say that I am a product of the Coffee House.”

As part of a chain of restaurants throughout India, Indian Coffee House would sell coffee and south Indian cuisine at an affordable place.

“Even strugglers could freely come in, have a cup of coffee,” Zareef says.

After its establishment near the Bund during the rule of Prime Minister of Jammu and Kashmir, Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad, it had fuelled the reading culture in Kashmir.

That was an era of progressivism and every writer was under the influence of Marxism.

However, their ideological inclinations were always motivated because it came with monetary benefits from Russia, Zareef says.

“To say the Coffee House was completely neutral from the politics is wrong,” he says. “They were comrades for a reason. There were free entrance seats in Russia for many. Only a handful of people were genuinely motivated and worked for a cause including Ghulam Rasool Nazki, Hamidi Kashmiri, Rashid Nazki, among others.”

But after it became a shut shop during the nineties, a vacuum was felt. Some scribes and writers who worked for New Delhi newspapers made Ahdoos as their new base, but not everyone could afford that place.

Apart from local legends, veteran painter MF Husain would be spotted with his artist friend Bansi Parimu inside the Coffee House every summer he would visit the valley.

“But if you think of that place and images of Eqbal Ahmad, Edward Said and Noam Chomsky pop up in your mind, you are completely delusional,” ZG Mohammad, celebrated columnist of Kashmir and the Coffee House regular, says.

“Still, it was a nice place. You could express yourself. Meet likeminded people and share your creative works with others. It is always necessary to have such places around.”

(Mehak Ayaz contributed to this story.)

To help us strengthen the tradition of quality reading and writing, we need allies like YOU. Subscribe to us.

Mountain Ink is now on Telegram. Subscribe here.

Become Our Ally

To help us strengthen the tradition of quality reading and writing, we need allies like YOU. Subscribe to us.

Muhammad Nadeem is a reader and writes about what he reads. Among his writings are reviews, poetry, and short stories. He also works with translation and criticism, and has previously been published in Prachya Review, Cafe Dissensus Magazine, Kashmir Lit, Sheeraza, Inverse Journal, AGNI, Poet Lore, 32 Poems, Jaggery Lit among other literary magazines and journals. His poems have been translated and published in several anthologies. His reading interests are diverse, and he has reviewed hundreds of books for literary publications. He is also a former editor of the Mountain Ink.