The ‘Shawl Girls’ Reviving Kashmir’s Classic Women Work Culture

Bisma Farooq is a Staff Writer at the Mountain Ink.

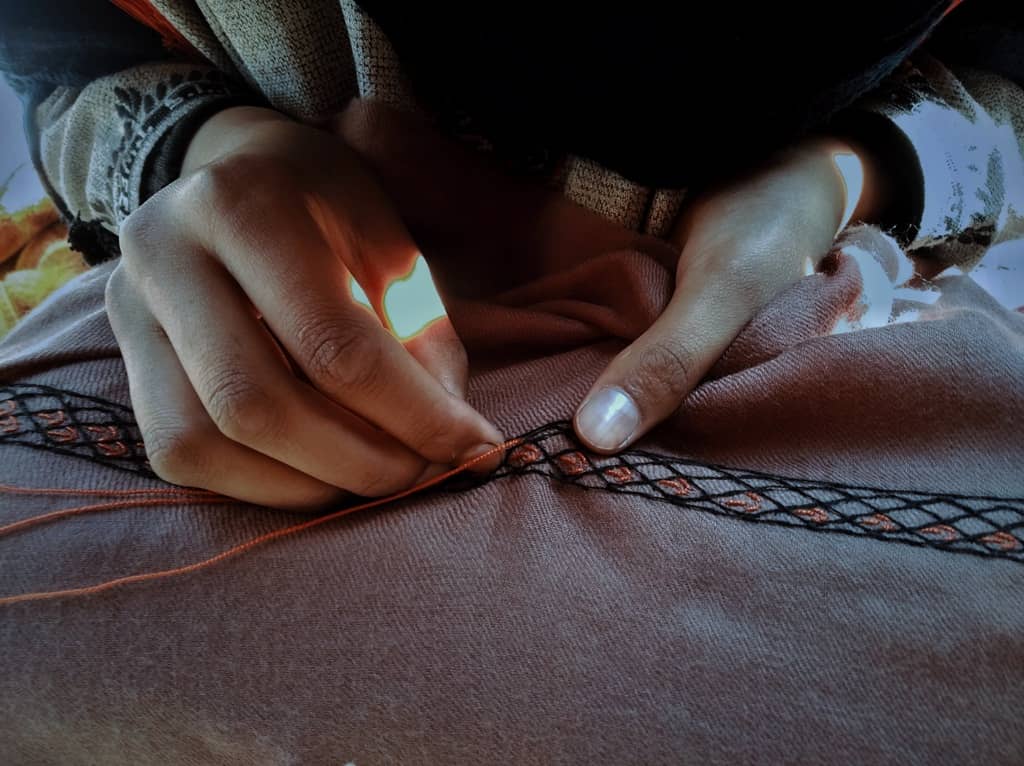

There was a time when many households served as vibrant workstations of the skilled women of Kashmir. After the tradition faded over the years due to the turmoil-hit market and lack of craft intervention, young and educated girls of Sonawari have now revived the old women workspaces with their collective efforts.

In the shade of a faded-green canopy, Asifa’s wait is only getting impatient.

It’s a misty morning in Sonawari’s Vijpara, and the pervasive pastoral look is conveniently hiding the rich ‘artisan abode’ image of this lettered parish. While the sun struggles with the clouds above, country dwellers sluggishly go about their routine in twos and threes.

Even as this footfall heralds a new day activity, Asifa’s wait only lingers on.

Before spring made her outings eager, the girl would enthusiastically step out in the snow and chilling cold, for the routine boosting the collective morale of the educated women of this north Kashmir’s sleepy village.

At around 10 am, 19-year-old Asifa waves at her friend, finally making her street appearance. She’s Humaira — the 21-year-old comrade of the collective cause.

Support Our Journalism

You are reading this because you value quality and serious journalism.

But, serious journalism needs serious support. We need readers like you to support us and pay for making quality and independent journalism more vibrant.

After exchanging smiles, the two girls walk past the bucolic symbols, structures and signposts. The duo gets involved in a pep talk while heading towards their uncanny workplace.

On their way, their strength surges to a near dozen. Khalida (25), Iffat (20), Zahida (16), Asifa (20), Nazima (18), Pakeeza (15), Razia (19) and others make it a merry band on the move.

Together, the girl group heads towards their friend, Bisma’s place, for serving the art and polish their craft skills.

There’s another thing they’re doing in the valley grappling with the educated, unemployed youth with their collective efforts. They’re reviving the routine which made their mothers and grandmothers sing their hearts out, while serving the shared skills within the four-walls of their home.

After making their chirpy entry into Bisma’s home, they sit on a sunlit porch. Apart from firepots, the warm workplace has a radio set playing songs of love and longing. They hymn together, and make the entire ambience lively.

“Having fun with work is what brought us together,” says Humaira, with a smile. “It only makes this shawl embroidery a labour of love for us.”

These girls became part of this collective embroidery affair at the fag-end of the plagued year of 2020. The motive was to come out of the lockdown-enforced confines, and engage in meaningful work and consoling conversation.

To make it a routine, the girls—either studying in school, or in college—had to strike a perfect balance between studies, household chores, and the group task.

Every day, these early risers first put their home in order, before bringing their own art pieces to the workplace, and make beautiful patterns with a needle and a thread.

The rise of this household group has only helped Vijpara to retain “an abode of artisans” identity.

Apart from housing carpet weavers and embroidery artisans, the village also has one of the highest literacy rates in the Sonawari belt. But some ten-thousand denizens—depending on handicrafts and agriculture—still grapple with blatant backwardness.

On their part, the girls’ collective is trying to flip that destitute image by fighting the odds together. The larger motive remains to lead by example and inspire others to play their part in the image-rebuilding.

“Today, most of us share a common thread and a healthy sense of competition and purpose in life,” Humaira says. “And this spirit is only helping our common cause.” яндекс

But, sadly, the outcome still remains worrisome.

Each girl makes around Rs 800 per month after getting a workpiece from local intermediates. While the low pay remains a long far cry in Kashmir’s fading art emporium, the girl collective also decry the meagre compensation for their skill slog.

“Apart from low-pay, we want to change the late-pay system in the sector,” Bisma, lifting her heavy gaze from her art piece, says.

“It doesn’t happen usually that we get a chance to contribute to the daily needs of the household because these intermediates don’t make payments on time.”

Challenges equally emanate from their homes—where their elders feel they’re flogging the dead horse.

For example, Bisma’s 38-year-old mother wants her to focus on something “sustainable” in life. A carpet-weaver herself, she says the ‘consuming’ craft she’s serving since childhood isn’t fitting for her recent class 12 pass-out daughter—who dreams to become a journalist.

“I want my daughter to fulfil her dream,” Chasfeeda, Bisma’s mother, says. “I’m working hard each day so that she can secure her college admission and excel in studies.”

But this disapproval is hardly stopping Bisma to revive what used to be a common scene in the valley of yore.

In the artisan-rich pockets of Kashmir, the womenfolk would assemble in the home of “Wouste bai” (master craftswoman) and together slog and stitch the glory — gracing the grand wardrobes and the big cashmere showrooms of the world.

However, as the strife became raged and dismantled the local artisan market due to the frequent lockdowns after the nineties, such household gatherings waned.

By reviving those bygone gatherings, the girl group has already become the craft interventionists apart from the new-age servants of the art.

Being educated and enterprising, the girl group is now seriously eyeing to make their artistic identity. Among them, Humaira is only going the extra mile with her embroidery endeavour.

“She brushes aside my constant complaining against her shawl slogging, as the same has started affecting her health,” says Rafiqa, Humaira’s mother. “My girl is just relentless in her pursuit.”

This resilience is already making the tribe thick-skinned. Even as some naysayers scoff at the group’s “vainglory”, the endless gossip is hardly derailing the combined commitment.

The eldest among them wears a sage’s stillness while making shawl patterns. While others in the group are keeping the flame of education burning, Khalida had to give up on her college due to poverty at home.

“I had to either live with that depressive destitution and continue the study, or save my sanity by starting earning for myself,” she says.

“Having said that, I’m not satisfied with myself yet, but then I’m learning and growing every day.”

Shy Pakeeza and Zahida are the youngest ones in the group. They work with the same enthusiasm as their elder group members. These girls are in school and dream of getting into a college where their art can get polished in a better way.

“I want to learn more about this art in college,” Zahida says while Pakeeza nods. “I want to know about its marketing and other related things.”

Every girl in the group has a dream to fulfil but limited resources and lack of marketing expertise is an obstacle. However, by challenging odds, they’ve already become harbingers of change in their part of the woeful world.

It’s already dusk and the radio is playing Lata Mangeshkar: “Yeh Kahaan Aa Gaye Hum, Yunhi Saath Chalte Chalte…”

Unmindful of the lyrics, Bisma rises up to turn the radio off, while waving the girls goodbye, with the promise of meeting again for the collective cause.

Mountain Ink is now on Telegram. Subscribe here.

Become Our Ally

To help us strengthen the tradition of quality reading and writing, we need allies like YOU. Subscribe to us.