Rana Safvi’s ‘City of my Heart’

Nawa Fatima studies Mass Communication from Jamia Millia Islamia, New…

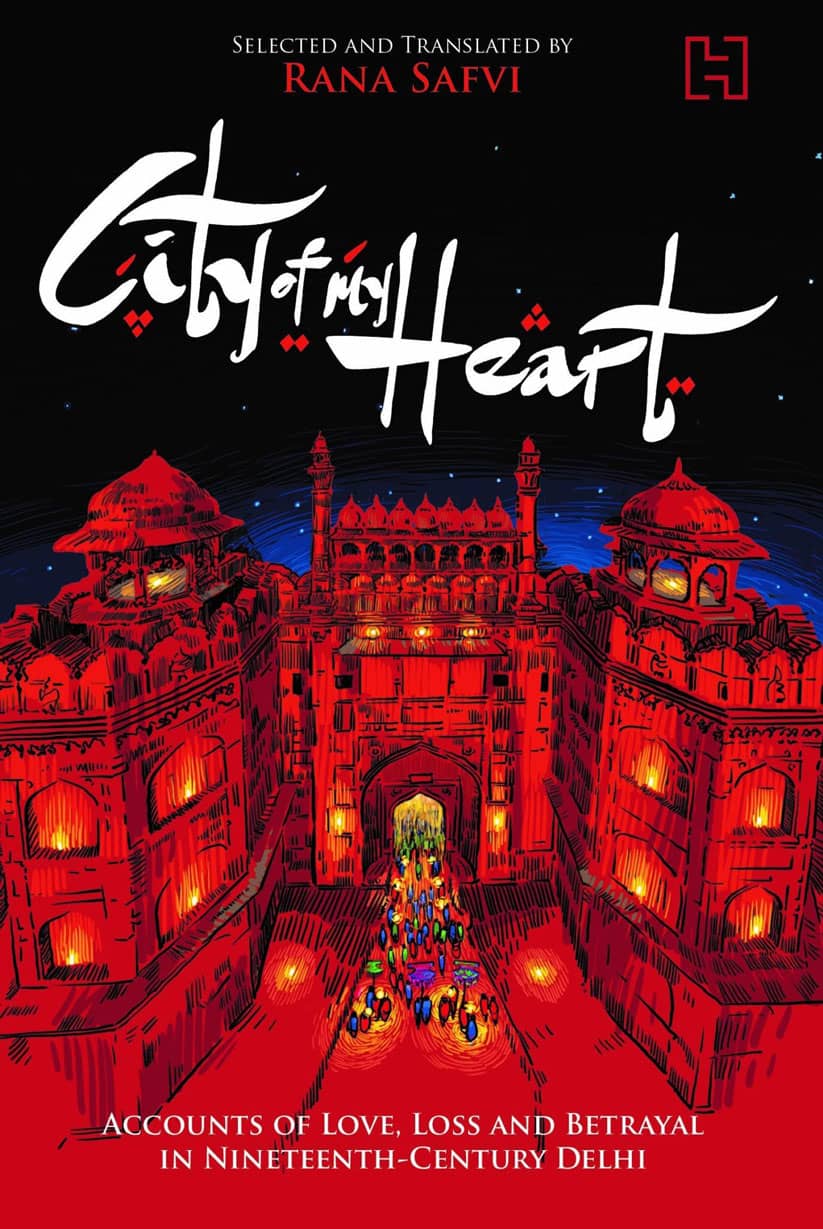

Beneath the modern metropolitan Delhi of today lie the remains of a royal Dehli which survived centuries. Rana Safvi, in her book, City of my Heart, digs up and translates some fragments of an era which could be attributed as magnanimous, more so, a golden period in the history of the Indian subcontinent. This book is an account of love, loss, and betrayal in the nineteenth-century Delhi. Safvi takes up four Urdu narratives to compile an English version which could have a broader audience at its disposal. The four pieces of work differ from each other in their tonality, yet a common royalty resonates among them, making this compilation a complete work in itself. The chronicles are placed perfectly in order, starting with descriptions of the Mughal lifestyle, proceeding with some first-hand experiences, only to end in a royal downfall. The work of Safvi has a grand narrative, retaining the essence of that period which speaks throughout the pages. It is a magnificent depiction of events which would almost deceive you to believe it as fiction, yet it is reality – the soul of a city that died in the mutiny of 1857. The lineage of Mughals might still go on, but surely not with the grandeur that it once exhibited.

The dilapidated sites of historic fascination that we witness today bloomed with life and vigour at one point, illustrating the Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb. Safvi has trapped this very spirit in her work, this originality and genuineness of people and culture that prevailed. It is hard to believe the contrast that Delhi has undergone in such a brief period of time. The transition from Dehli to Delhi is what Safvi throws light upon. The first part of this book is a translation of ‘Dilli ka Aakhri Deedar’ (The Last Glimpse of Dilli) by Syed Wazir Hasan Dehlvi. This portion is a description of the simplicity and ease of life which existed during the nineteenth-century Dilli. There was a freshness in the aura which dispersed from the Qila to the common folks. Work was divided well and people were content with their lives. There was a respect – not fear – for the leader. Hasan Dehlvi also includes an account of life during the Mughal era as narrated by Nani Hajjan, a mughlani who lived in the Qila. She represents the few witnesses who have survived the mutiny and recounts tales of yore. Her words have an undertone of misogyny which could have been prevalent during those times. Thus, this part is layered and twice distanced in narration, which travelled from Nani Hajjan’s stories to Hasan Dehlvi’s writings, to be finally translated by Safvi.

‘Bazm-e-Aakhir’ (The Last Assembly), by Munshi Faizuddin is the second narrative to be included by Rana Safvi. Faizuddin spent a lot of time in the Qila as an attendant and was aware of the inner workings of the court, hence he was in a unique position to write a tribute to the Mughal court as it was. This is a chronological account of all the festivals that were celebrated during the era. The timeline of all the celebrations that were held is cited in detail. There are also depictions of the routine that was followed by the Badshah and others. The portrayals of a royal morning, afternoon, and night, with all the activities that revolved around them find their mention here. The delicacies that were served in the royal court are also described greatly. The book places the Badshah as a religious man who was a great follower of traditions. These rituals and customs which descended down from the royal court can be traced in various Muslim households even today.

Mirza Ahmad Salim ‘Arsh’ Taimuri’s ‘Qila-e-Mu’alla ki Jhalkiya’n’ (Glimpses of the Exalted Fort) lines up next to find its place in this translation. Taimuri was himself a descendent of the last Mughal Badshah, Bahadur Shah Zafar – born in the fifth generation of his lineage. He was neither born nor brought up in Delhi and most of the historical accounts he presents are based on hearsay. Taimuri is grateful to his father Hazrat Labeeb who has recounted some unique events for him to pen down. This part unfolds itself in the definitions and brief descriptions of the royal court. Taimuri defines various customs that prevailed then, right from the food eaten to the punishment served. This part is further divided into eight sub-units, each dealing with a different aspect of life, to document the twilight years of the Mughal era. Taimuri includes small qissas (stories) of notable people which he felt worth mentioning. The account also lists the names of sons and daughters of the Badshah and the fate they served. Thus, he establishes a lineage which could soon to be forgotten. It is in this part of City of my Heart where the Britishers intervene. In a very brief course of events, Taimuri describes the mutiny of 1857, the exile of Bahadur Shah Zafar, and the extinguishment of the Mughal dynasty.

City of my Heart’s final narrative is ‘Begamat ke Aansu’ (Tears of the Begums) by Khwaja Hasan Nizami. There could not be a more perfect ending to this compilation than this heart-wrenching account by a princess called Sultan Bano. This chronicle plucks the chords of our emotions to reveal the tragic story of a royalty in decline. It depicts the Mughals after the mutiny of 1857. The Mughal rulers, in a twist of fate, were forced to turn into royal beggars since their aristocracy would not perish even in such times of despair. This portion of the book depicts a strange irony that is life. It places you high on top only to make your downfall greater. The book has accounts of various descendants of the emperor, who would not even think in their wildest of dreams of such a decline. From velvet cushions to thatched beds, the lineage of the Badshah witnessed a full swing of highs and lows. It vividly documents stories of various princes and princesses after the fall of the empire, of their fate which toppled over, and of what was left behind – mere nostalgic reminiscences of a once-pertinent glory.

Support Our Journalism

You are reading this because you value quality and serious journalism.

But, serious journalism needs serious support. We need readers like you to support us and pay for making quality and independent journalism more vibrant.

In four volumes of narratives, City of My Heart captures nineteenth-century Delhi in its entirety. Rana Safvi has very particularly selected, placed, and translated these works to present a correct picture of that time. It depicts the rich cultural, social, and political milieu which is often defamed by historians. On a metaphorical level, the book is a reminder of the transient nature of life which spares none.

Mountain Ink is now on Telegram. Subscribe here.

Become Our Ally

To help us strengthen the tradition of quality reading and writing, we need allies like YOU. Subscribe to us.

Nawa Fatima studies Mass Communication from Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi.