The Matron Who Empowered Women, Nurtured Orphans

Aaliya Shalla is a trainee staff writer at the Mountain…

She may be known for her museum of love, but Atiqa Bano of Sopore was more than a curator of the past. She was an unassuming philanthropist and the community crisis manager who silently fought destitution till her death.

A decorated gallery of awards and recognitions makes it a wall of fame. But beyond this credit countenance, the place works like a time-machine — transporting one back to the era when life was devoid of cosmetics. Packed with antiques and antiquity, the curated world hosts visitors for a past time.

The buzz and bustle is there despite Atiqa Bano’s museum already a much-explored and talked-about memorial. Much of this response has to do with her benign personality.

That the lady from the town cindering akin to war-movies during upheavals rose up to become the community campaigner is still commanding a respect. And then how the same campaign threatened to lose its cause once she departed.

Years later, the matron who gave Kashmir its privately-curated heritage museum is still alive in the mission she spearheaded during her eventful life.

Post-Atiqa Bano, the keys of Meeras Mahal lies with her nephew, Muzamil Bashir.

Support Our Journalism

You are reading this because you value quality and serious journalism.

But, serious journalism needs serious support. We need readers like you to support us and pay for making quality and independent journalism more vibrant.

Dressed in a blue shirt, grey pants and black shoes, Muzamil is an expressive man counting the contribution of his aunt like a captive chronicler.

At a certain point in the conversation, his phone rings, with a caller inquiring about Atiqa Bano’s upcoming anniversary. “Yes, we’re organising an event on October 4.”

It was on that day, four years ago, the Meeras Mahal lost its compassionate curator.

Atiqa Bano was born seven years before India got independence. Her father passed away when she was two. A member of the Muslim League, he was a jail-bird who died, during one harsh winter, due to Tuberculosis in his cold cell.

Her mother singlehandedly raised and encouraged her to attend school and later college in Srinagar. She obtained two Masters—one in Economics, other in Urdu—from Rajasthan’s Banasthali Vidyapeeth University.

“When my aunt was young, she had no paper or pen,” Muzamil recalls. “She used to write on the windowsill with a piece of coal. And, when no space was left on it, she used to coat it with mud and re-write.”

Years later, when she was appointed as a teacher, a lot of suitors in town came forward with a marriage proposal.

“But she chose none,” Muzamil recounts. “She was left disheartened by society’s hypocrisy. When she was jobless, not even a single person had come forward to marry her. This hit her and she decided to dedicate all her life to the welfare of orphans and widows.”

Atiqa Bano started her career as a teacher in 1958 and went on to become the joint director of education in 1994. She travelled to different parts of Kashmir, during her tenure as a district officer and schools inspector. She saw the diversity of Kashmiri culture and loved it. She wanted to preserve it.

Later, she would retire as the first woman director of Libraries and Research, Jammu and Kashmir, in 1999.

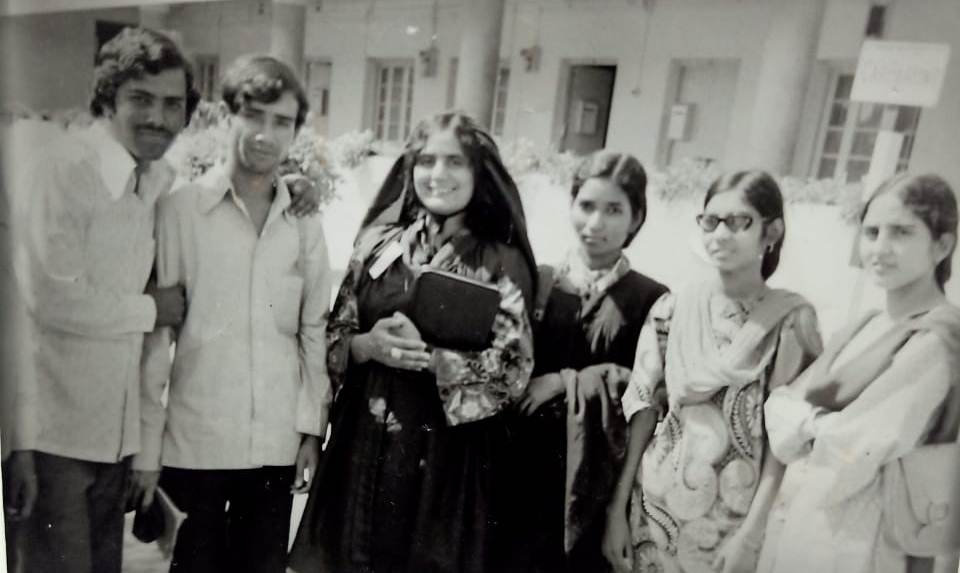

Atiqa Bano led a simple life. A black burqa was her signature dress. She even used to sew her burqa by herself. “She used to buy clothes and jewellery for others, but has never worn a single piece of jewellery herself,” Muzamil says.

Instead of a purse or a handbag, she carried a book, pen and notebook in a paper or polythene bag. She would love to eat collard greens to honour the memory — how her poor family once had nothing to eat except haakh.

She loved gardening. It was her morning ritual after Fajr namaz. She even used to cut the grass herself.

“As long as she was alive, we never needed a gardener,” her nephew says. “We had around 300 flower pots at home and she used to water them all in the morning, using a bucket and jug.”

After that, she would have her favourite nun-chai with soft chapattis in breakfast.

While leading this austere life, Atiqa Bano founded Majlis-e-Nisa, the first-ever organisation for the welfare of women in Sopore, in 1973.

Women learnt knitting, stitching, calligraphy, also Quran and Islamic education there.

The motive, Muzamil says, was to empower women and make them independent.

Later she realized that only skills are not enough—as people need to learn western education as well. And for that, she established Al-Mustafa school in Sopore.

“But it was destroyed in a fire,” Muzamil continues. “And due to financial instability, she couldn’t renovate it.”

However, when Islamia College for Women was burnt down in the 1993 Sopore Massacre, she fought pitched battles with the Auqaf Committee Sopore for it.

“Auqaf’s decision to build shops instead of rebuilding the campus for women disheartened her and made her hate politics,” Muzamil says.

“And due to this, when the political parties—NC, PDP and Congress—asked her to join their parties and promised her Education ministry, she refused.”

But as a champion of women’s rights, Atiqa didn’t stop her women welfare works. Starting her Kashmir Women’s College at Noorbagh, Sopore, in 2001, she taught women how to maintain accounts and finance.

“She believed that the world would be a better place if we educate women about their rights,” the nephew says.

At college, she treated peons, clerks, teachers, administrators all alike. During the lunch break, she made all the employees sit and eat together.

“While hiring college staff she gave preference to women candidates. She loved to see women being independent and living life on their own terms,” Muzamil says.

Soon after her retirement, she started collecting historical and cultural artefacts and established a heritage museum named Meeras Mahal at Sopore.

The museum established in the year 2001 holds more than 5000 artefacts including coins, dresses, jewellery, ornaments and miniature armaments, agricultural tools, earthenwares, copper and brass utensils, pots and pitchers, willow baskets, handicrafts, spinning wheels, handwritten Qurans and much more.

“She used to write journals and I’ve her diaries that she had written from 1958 to 1999. A few of them are missing. I’ll publish them as soon as I get hold of all of them,” Muzamil says.

But when the same sound lady was diagnosed with cancer in 2017, it shocked countless lives she had touched. At Delhi’s Apollo hospital, she was asked to undergo surgery. But she was reluctant.

“She called me and said, ‘Don’t waste this money, we can marry off poor girls with this.’ She repeated the same words when I tried to buy her a new blanket at her deathbed,” Muzamil recalls.

But somehow, she was convinced to undergo the surgery for the sake of the orphans and the widows who looked up to her.

Much of her silent welfare works would surface when a group of burqa-clad girls came and wailed in women tent on the day of her demise. Nobody knew them, until Muzamil checked their identity.

“You don’t know us, but we know you,” they told Muzamil. “We’re orphans and Atiqa Ji used to take care of us. She didn’t want us to share it with anyone.”

Another mourner came from Bandipora, informing Muzamil how Atiqa Bano took care of her family after her husband was killed. She even got her daughters married.

“I don’t need anything now,” she told Muzamil. “My son earns and takes care of me. But at the time of need, she did for me what no one else could.”

After that, Muzamil stopped asking unknown mourners who they were, and how his aunt touched their lives.

Mountain Ink is now on Telegram. Subscribe here.

Become Our Ally

To help us strengthen the tradition of quality reading and writing, we need allies like YOU. Subscribe to us.

Aaliya Shalla is a trainee staff writer at the Mountain Ink. She is a pass out of Multimedia & Mass Communication from the Govt. Degree College, Baramulla.