The Life of Poet—Louise Glück—in One Poem: The Wild Iris

Muhammad Nadeem is a reader and writes about what he…

Stephen Dobyns, writing in the New York Times Book Review, said, “no American poet writes better than Louise Glück, perhaps none can lead us so deeply into our nature.”

I cannot love

what I can’t conceive, and you disclose

virtually nothing…

Part I

Louise Glück is one of America’s most honoured contemporary poets. In 2020, Glück has become the first American woman to win the Nobel prize for literature in 27 years, cited for “her unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal”.

Glück is the 16th woman to win the Nobel, and the first American woman since Toni Morrison who took the prize in 1993. The Nobel poet is the successor of famous American singer Bob Dylan who won the Nobel Prize in 2016. She’s the winner of the Pulitzer Prize and the author of a dozen widely acclaimed books.

Stephen Dobyns, writing in the New York Times Book Review, said, “no American poet writes better than Louise Glück, perhaps none can lead us so deeply into our nature.” Pulitzer Prize winner Robert Hass has called her “one of the purest and most accomplished lyric poets now writing.”

Support Our Journalism

You are reading this because you value quality and serious journalism.

But, serious journalism needs serious support. We need readers like you to support us and pay for making quality and independent journalism more vibrant.

In 2003, Glück was named the 12th United States Poet Laureate. That year, she was named the judge for the Yale Series of Younger Poets. She served in that position through 2010.

Glück taught at Williams College for 20 years and is an adjunct professor of English and Rosenkranz Writer-in-Residence at Yale and Visiting Professor with the Stanford Creative Writing Program. She was elected a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets from 1999 – 2005, and is currently a member of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters.

Glück attended Sarah Lawrence College as well as Columbia University but did not obtain a degree.

As her work took roots and blossomed over the decades into its variegated forms, awards and honours rained down steadily on the poet.

Gluck’s Faithful and Virtuous Night, won the 2014 National Book Award for Poetry. A Village Life (2009), which was shortlisted for the International Griffin Poetry Prize, and Averno (2006), which was nominated for the National Book Award, won the L.L. Winship/PEN New England Award and was listed by The New York Times Book Review as one of the 100 Notable Books of the Year.

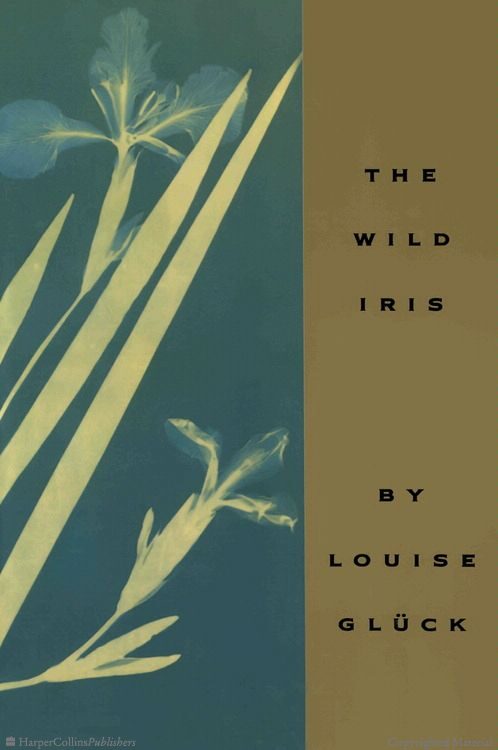

Her earlier work includes The Seven Ages (2001); Vita Nova (1999), winner of The New Yorker Magazine’s Book Award in Poetry; Meadowlands (1996); The Wild Iris (1992), which received the Pulitzer Prize and the Poetry Society of America’s William Carlos Williams Award; Ararat (1990), which received the Rebekah Johnson Bobbitt National Prize for Poetry; and The Triumph of Achilles (1985), which received the National Book Critics Circle Award, Boston Globe Literary Press Award, and the Poetry Society of America’s Melville Kane Award.

The First Four Books of Poems (1999) collects the early work that helped establish Glück as one of America’s most original poets. Her book of essays, Proofs and Theories (1994), was awarded the PEN/Martha Albrand Award for Nonfiction. Her most recent book of essays is titled American Originality.

Part II

At the end of my suffering

there was a door.

Glück works on diversifies themes, such as trauma, desire, death, loss, rejection, the failure of relationships, greater appreciation of life, attempts at healing and renewal, nature, recoil and affirmation, sensuous immediacy, reflection, awareness of mortality, strenuous self-interrogation, Celestial Music, loss of innocence, status, power, morality, gender, language, sadness, an aura of iconoclasm, in-betweenness, isolation, sense of an ending, desire for love and attention, ethnic identification, religious classification, gendered affiliation, among others.

Hear me out: that which you call death

I remember.

Overhead, noises, branches of the pine shifting.

Then nothing. The weak sun

flickered over the dry surface.

Glück’s work is noted for its emotional intensity and technical precision; her language, staunchly straightforward, is clear and refined, so-much-so one does “not see the intervening fathoms”.

The aesthetic challenges abound for a writer whose vision of reality is just that: a vision, mysterious, liable to dissolve. Glück has long sought, in her volumes of poetry, imagined worlds broad and porous enough for real people, strangers and intimates alike, to wander around inside them. The effect is like a lucid dream where real decisions are worked out in an alterable realm.

It is terrible to survive

as consciousness

buried in the dark earth.

Louise Gluck’s “The Wild Iris” tries to answer the questions “Who am I?” and “What is the nature of God?”

Most of the poems use a flower as both metaphor and indirect subject, yet the collection is more like a record of the speaker’s prayers. Readers unfamiliar with Gluck’s crisp, a sparse language may have difficulty finding their way into these poems.

The first few pages do not provide enough of a narrative, and it would be easy to conclude that the writer’s vision is too personal and cryptic for others to share. Gluck begins her first poem The Wild Iris with the assertion, “At the end of my suffering/ there was a door.” It’s a fascinating lead, yet the second stanza reads, “Hear me out: that which you call death/ I remember.” Such assertions are hard for readers to grasp and are a risky move at the beginning of a book.

Glück is known to depict emotional intensity in a frequently drawn myth, as well as history, nature, aspects of trauma, desire, as well as a mythology to impart her meditative mind based on personal experiences and modern day to day life. She also drew her characters based on mythological depiction from Persephone and Eurydice, among others.

You who do not remember

passage from the other world

I tell you I could speak again: whatever

returns from oblivion returns

to find a voice:

In The Wild Iris, her subject is the triumphant return to expression. In the new sequence of poems, she writes about the frightening condition of lying fallow, one day after another, without the prospect of renewal.

Glück’s poems can also be thought of as expressions of a very particular and troubled person, a poet determined to get to the bottom of her own experience without making an idol of “reality” or brute suffering. Her poems at their best—and they are very often at their best—embody not just the rage to order, but also the rage to identify a “truth” that no order can approximate or touch.

The Wild Iris was indeed a turning point for its author, a woman known for both her thematic obsessions and her distinctive use of language. Perhaps more important, the book tackles questions that need to be addressed both in the artistic community and in society at large.

Gluck’s conclusion, at least concerning the frailties of the physical world and the garden she cultivates with her husband, is found in her poem The White Lilies:

Hush, beloved. It doesn’t matter to me

how many summers I live to return:

this one summer we have entered eternity.

I felt your two hands

bury me to release its splendor.

The evolving self, constantly subject to revision, is composed of different voices, is most safely explored on the page, yet to enter language is to abandon human relations. Gluck records the process of creating the self. The poem explores the tentative movement from emotional isolation to humanity.

For Gluck, leaving the safety of the mind for the page is a risky endeavor for even something as controlled as the poetic lyric possesses the power to expose too much of the self, thus inviting vulnerability. Yet the desire for intimacy requires action, and Gluck accomplishes this through the form of the poem. It is the tension between what can and cannot be said, through the possibilities and limitations of language that Gluck explores being and non-being.

Though one would never think to say of her work that it represents a triumph over reality, the poems often refuse to abide by the decorums associated with realism or straightforward first-person lyric.

Then it was over: that which you fear, being

a soul and unable

to speak, ending abruptly, the stiff earth

bending a little. And what I took to be

birds darting in low shrubs.

It’s not simply that Glück is adept at speaking in the voices of flowers but the point is that reality has existed for Glück simultaneously as foundation and irritant. She acknowledges what seems to her indisputably true—like the fact of death, or the loss of love—while refusing to concede that the soul is merely what Wallace Stevens once called a “rustic memorial of a belief” long consigned to irrelevance. Fierce in her determination to see things as they are, she fashions poems that suggest how much more there is to know than she can say.

Incorrigibly committed to lucidity and alert against even the slightest imprecision, she ventures in and ventures out as if full comprehensibility were a chimaera and an obstacle to true understanding.

from the center of my life came

a great fountain, deep blue

shadows on azure seawater.

In the foreground, larger than the rest, we may find events from the distant past, while in the background what happened yesterday is blurred and foreshortened. The distinctions between past and present, between the actual and the invented, are levelled, as is the distinction between the experience of reading (or writing) the book and that of encountering oneself inside it.

(This Feature appeared in the October 2020 print issue of the Mountain Ink.)

To help us strengthen the tradition of quality reading and writing, we need allies like YOU. Subscribe to us.

Mountain Ink is now on Telegram. Subscribe here.

Become Our Ally

To help us strengthen the tradition of quality reading and writing, we need allies like YOU. Subscribe to us.

Muhammad Nadeem is a reader and writes about what he reads. Among his writings are reviews, poetry, and short stories. He also works with translation and criticism, and has previously been published in Prachya Review, Cafe Dissensus Magazine, Kashmir Lit, Sheeraza, Inverse Journal, AGNI, Poet Lore, 32 Poems, Jaggery Lit among other literary magazines and journals. His poems have been translated and published in several anthologies. His reading interests are diverse, and he has reviewed hundreds of books for literary publications. He is also a former editor of the Mountain Ink.