‘She Has Become Shy, Scared’: How Screen Is Shaping Budding Kashmir

Basit Parray is a trainee staff writer at the Mountain…

Khan Waqas is a bachelor's student of Journalism and Mass…

Children of Kashmir are staring at yet another hostage period after the inferred third Covid wave made offline classrooms a primary casualty of the official Covid response.

Shamshad Akhtar’s fears have returned to unsettle her daily chores and mental calm.

Last night, hours after Kashmir administration announced yet another educational curtailment calendar to keep the rising covid cases in check—notwithstanding the growing public grouse about the free-flowing tourist arrival and other thriving social activities in the valley—she couldn’t sleep a wink.

Apart from making her restless, the controversial decision to send students in protest mode has only derailed her daughter’s normalized educational routine.

“Battle of nerves has returned to haunt me,” Shamshad made a curt remark about the reimposition of curbs on coaching centres.

“It’s always a slog to keep your child normal within the plagued walls of the home. I don’t know how long this jinx is going to ground our children.”

Support Our Journalism

You are reading this because you value quality and serious journalism.

But, serious journalism needs serious support. We need readers like you to support us and pay for making quality and independent journalism more vibrant.

Shamshad’s daughter last went to school in 2020—just for two days.

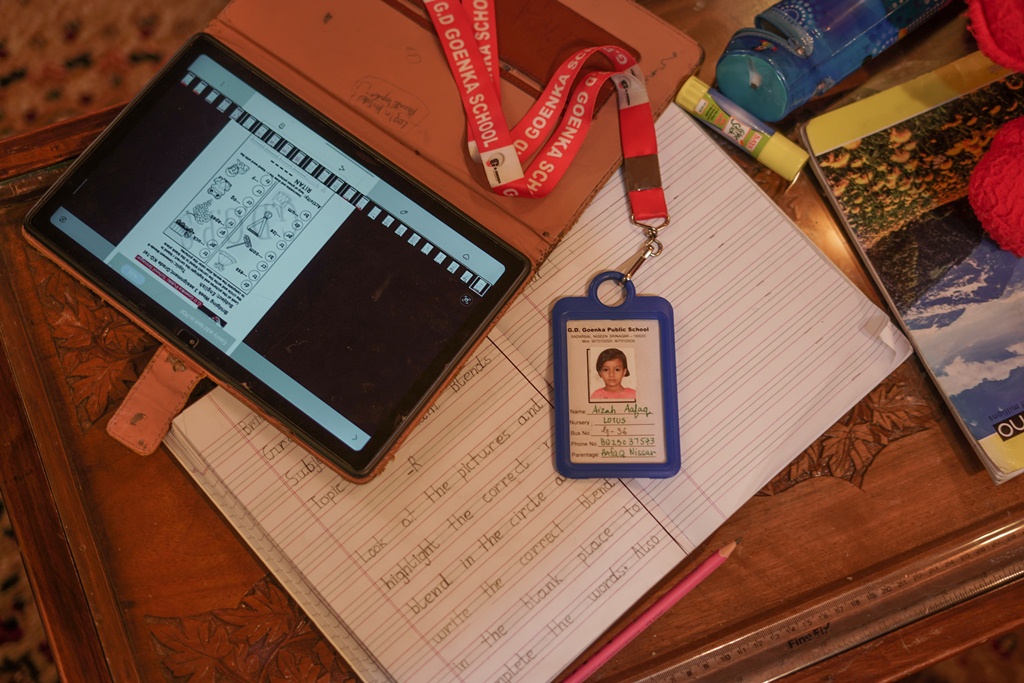

With the subsequent campus closure, this mother discovered how online classes don’t work with kindergarten-aged students.

“Kids need essential play-based learning that-in- person kindergarten provides and lays a foundation for comprehension skill,” Shamshad opined.

Since 2019, the crippled campuses have redefined the idea of education for Kashmir’s small children. As per experts and parents, the budding Kashmiris are undergoing progressive erosion of confidence and self-esteem that may eventually overshadow their career prospects.

And with third-wave imposing fresh study sanctions, it’s further feared to create acute learning gaps that schools were supposed to fulfil.

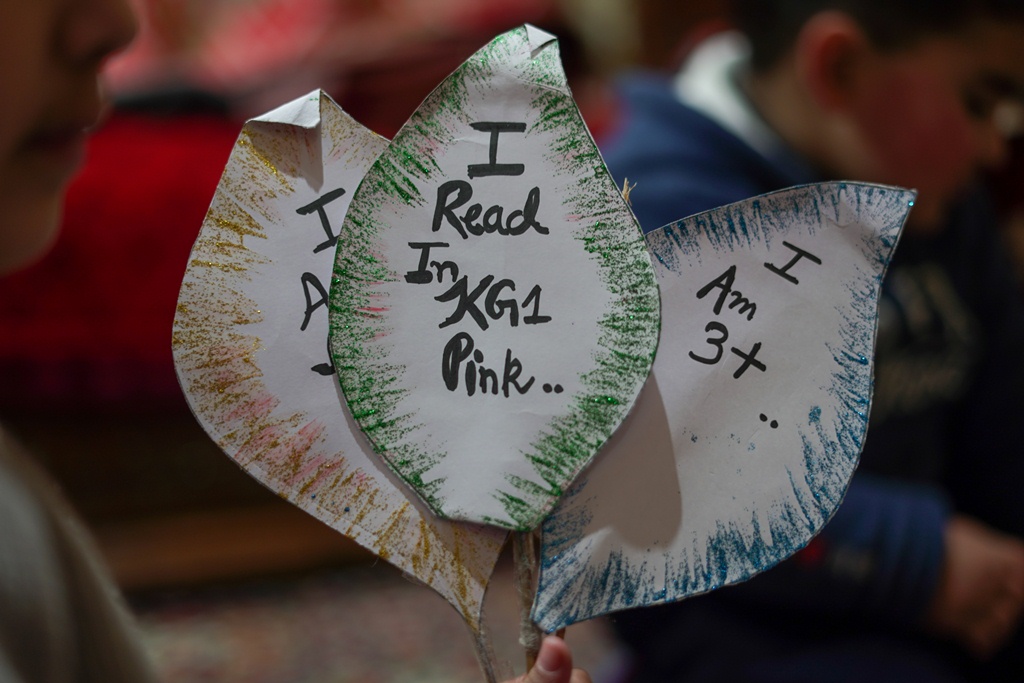

Little Naira Shah is already living that forecasted fear.

For the last two years, this first-grade student hasn’t seen the school. She’s unable to visualize her campus and class. When asked by someone from which school she’s from, she says with her head down, “I’m in first-class.”

Her mother, Kousar Nisar, said Naira’s shyness and doubts are escalating every day. All she knows is taking a smartphone in the morning and giving online classes until 2 pm.

“In terms of the level of comprehension as well as social skills, she lags behind her elder siblings,” Kousar said.

Noting these learning disabilities, a report by the Annual Status of Education Report 2020 (ASER) has highlighted the drop in reading comprehension for kindergarten and class-first students during the pandemic.

“Naira doesn’t talk to anybody except her family,” Kounsar continued. “Those are the only people she knows and talks to. She’s shy and scared talking to strangers, unlike my other two children.”

When asked what she wants to become in the future, little Naira replies, “Mjhy ghr pae rehna hae, subha thoda kaam karna aur pher tv dekhna hae” (I want to stay at home, do household chores, and watch TV).

The ASER report also emphasized that online education did not work for all.

“While smartphone availability in homes almost doubled from 2018 to 2021, with 67.6 per cent of students on average had a device at home, but over a quarter of them had no access to it at all,” the study mentions.

On the face of these findings, Manzoor Ahmad, a parent, offers his two cents: “Our education system is slow to move at the best times, but now requires a wartime effort of agile innovative and focused urgency to mobilize adjusted education for children during a one in century pandemic.”

Mindful of his daughter’s deficits, Manzoor saw her struggling with the screen study during covid.

“She didn’t have much going on with reading fluency,” he said. “During the pandemic, it was gruelling to go through that schedule. But with extra effort from teachers and parents, we tried to fill that learning gap. But yes, it never helped that much.”

Between this hopeful and hopeless pursuit, the kindergarten and Class-I kids of Kashmir hardly had a moment to feel the real classroom ecosystem. It has also made them delusional about class assignments.

“I had a conversation with my kids lately about an assignment for another class,” Samiya Jabeen, a kindergarten school teacher, said. “They just broke down a little bit. Most of these kids aren’t motivated anymore. The pandemic changed them. They should be given more time. There’re a lot of things in which children find difficultly due to staying at home and I can’t get a hold on it.”

Samiya thinks teachers are trying to jump back into it and get kids of kindergarten back into the practice of having deadlines, learning and having standards and expectations.

“But we’re living in unprecedented times,” she said. “Maybe they’re going to ease in a little differently than in the past. Teachers certainly will have to adjust some of our pedagogy, and extended deadlines might just become a norm, or have more flexibility about how kids are able to complete assignments and learn.”

The ASER report suggests fundamental skills need to be picked up again — like reading, comprehension of mathematics, so that kids of kindergarten can cope up with the current curriculum.

“Gaps left in foundation years could hamper the kids’ physical and mental development, besides social skills,” argues Adil Fayaz, a programme coordinator of Child Guidance and Wellbeing Centre, IMHANS- Kashmir.

“In the age when they need lively school exposure for personality development, kids are confined to their homes. They’re scared to speak and interact with people and later develop a social phobia.”

Parents who come to visit IMHANS often tell Adil that their kids have anger and confidence issues.

“When hopefully this situation is over and we restore to traditional schooling, we need to make sure to give space and time to get these children to adjust, forget about the syllabus for some time and focus on these issues,” Adil said.

The lurking fear, experts say, is that these kindergarten kids are likely to underperform through elementary school and maybe high school.

But Bisma Manzoor, a teacher, believes that kids can pick up quickly if they start doing the appropriate things.

“This is not a permanent situation where you’ve kids that have got stuck and cannot get out,” she said. “We teachers and school system have to unstick ourselves from the grip the curriculum has on us. I’m going to start with the kids and how can I make the education system much more aligned with the needs of the child.”

This positivity apart, the pandemic isn’t over yet. And it’s not unfathomable to visualize shut schools for more time.

While switching back to an online mode of disengagement exacerbates learning loss, experts fear, this problem will accumulate and intensify like the virus that caused it, if the course correction doesn’t arrive soon.

Mountain Ink is now on Telegram. Subscribe here.

Become Our Ally

To help us strengthen the tradition of quality reading and writing, we need allies like YOU. Subscribe to us.

Basit Parray is a trainee staff writer at the Mountain Ink. He is a bachelor's student of Journalism & Mass Communication at the Cluster University, Srinagar.

Khan Waqas is a bachelor's student of Journalism and Mass Communication at the Cluster University, Srinagar. He is currently a multimedia intern at the Mountain Ink.