On the Streets of Srinagar

Sharafat Ali is an independent photojournalist based in Kashmir. He…

+9

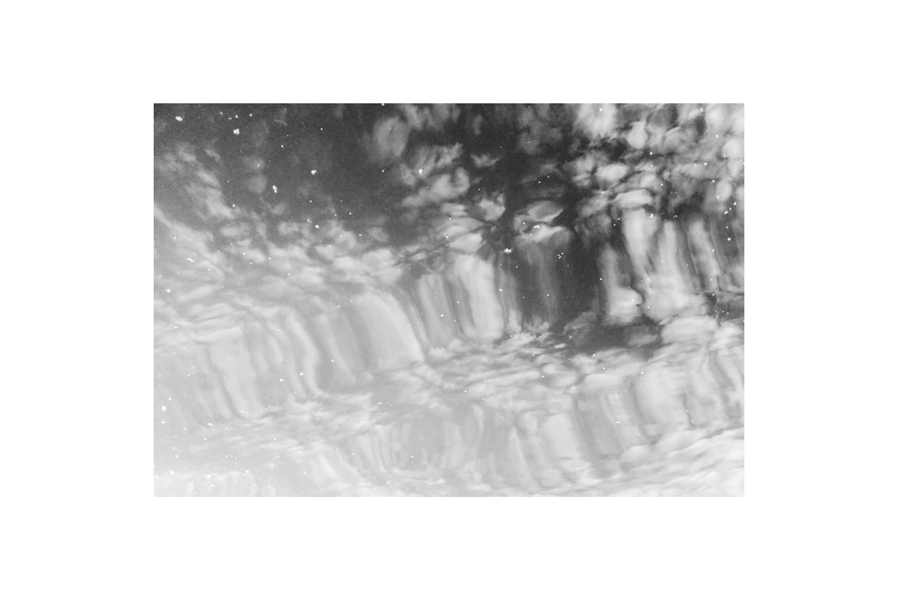

+9 Beyond landscape, there’s always mindscape and that is what a shutterbug is trying to capture in this deeply personal account.

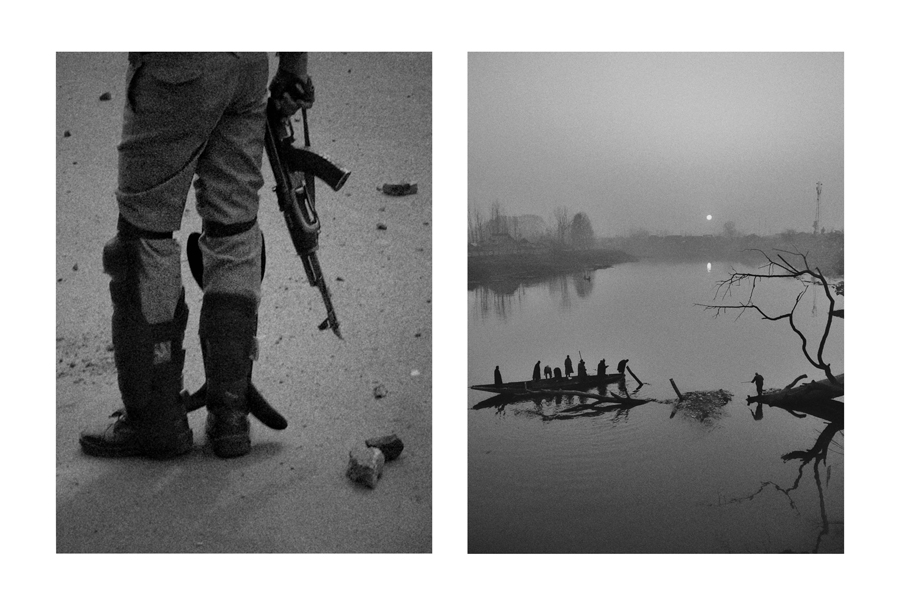

It’s not a glitzy undertaking to be a lensman in Srinagar — the city where empires perished, where romantics are oral legends, and where every soul has a staggering saga to share. As a citadel of glorious fables barring treachery of times, the city is the graveyard of reputations.

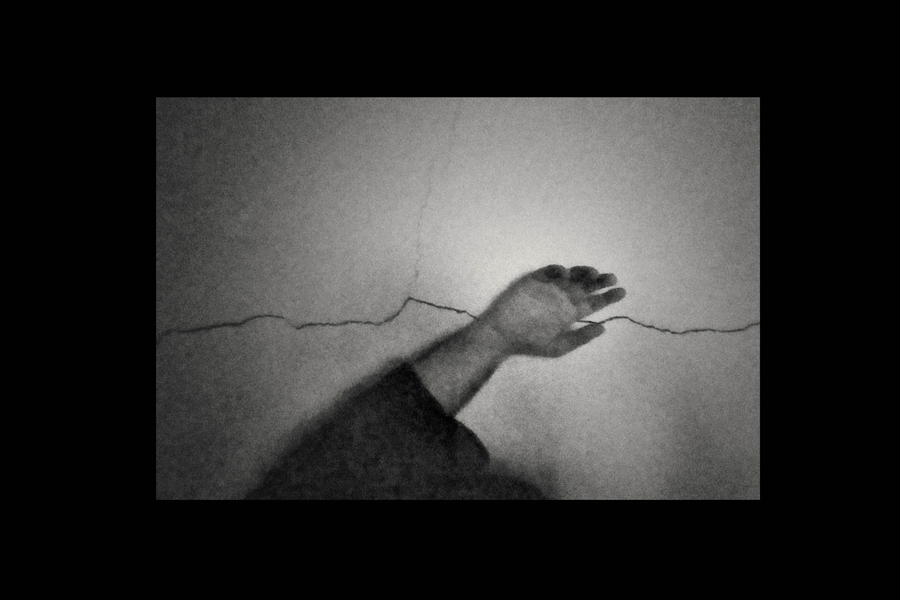

I often frequent the stricken streets for some life glimpse. The wan-masonry of what once was the Venice of East is now a notional ‘ghetto’ bearing the brunt of the conviction.

It houses pain and pathos, and yet sparkles with resilience in hope of a new dawn.

But somewhere in those mugged lanes, I keep on bumping into some obscure characters. They were once history makers, but now, reduced to a pale shadow of their bygone days.

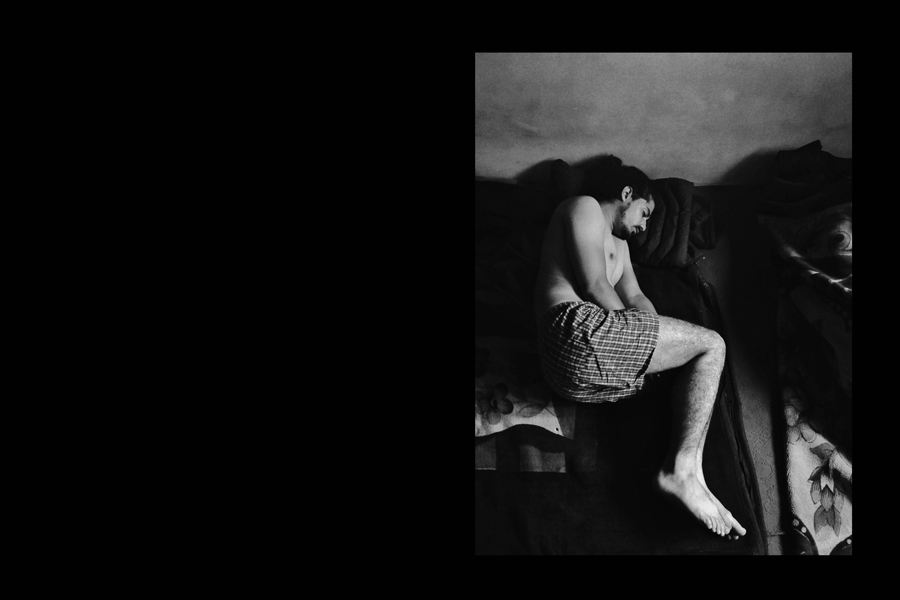

I spotted this limping hawker in cityside many moons ago. They call him a hothead of halcyon days who went for what his tribe believed the salvation trip, only to return distorted.

Support Our Journalism

You are reading this because you value quality and serious journalism.

But, serious journalism needs serious support. We need readers like you to support us and pay for making quality and independent journalism more vibrant.

The man is now an object of pity, and far from his legendary past.

He makes his living like a comatose commoner at the sprawling cemetery housing among others his childhood playmates.

But then, the city, as I’ve captured it, isn’t only about the stonewashed Salvadors. It’s equally about those who suffered the history. Akin to the halted time in the Red Square’s clock tower, most of them now struggle for the tick and pulse.

This realization of one’s roots is disquieting. It reminds you about your forefathers, hanged from one of those of seven bridges in Srinagar. It jogs your memory about those noble men of your homeland who had halted the viceroy’s water ride, right under the nose of that severe sovereign, to send a clear message: “They’ve no business here.” And best of all, it reminds you about those times when captives crowded the streets for some free will.

But when the deadly virus even locked the gates of shrines in Srinagar, I saw traumatized struggling for some spiritual solace. In times when social untouchability has created new mental distress, they were craving for the consoling company of “god’s own”.

In the same anguished city, I once met a roaming rhymester. The city is grief, he said, bereft of its wicked viziers, now tasting their own toxin.

But he lamented over Srinagar, the cradle of chronicles, for becoming a mother’s perpetual windowsill wait for her son.

It was a strange feeling, he said, as we stopped by a stall to have a cup of tea.

Seeing myself surrounded, I was in a state of shock. Pathetic. I was afraid. What exactly is going to happen next? I had no idea. It was a colourless, cold night. I felt a strong shiver in my bones. I was not able to think. It all just stood still.

I did not complain, yet the sky threw flares of lightning and thunder. The horses were running off the road. I, too, wanted to run. But I was caught by the night.

The night was dark. Not as dark as their hearts. I was in deep trouble. It was different this time. It was real. The helplessness was creeping into my heart. I was so sure of my death. Their knives and the other weapons were hungry for my flesh, thirsty for my blood. They were just doing their duty.

The time started to slow down. It all came back. My brain brought back all the memories about my childhood, family and friends. It was time. They put a mask on my face and dragged me. I had heard the stories. Thousands of them. Now it was my turn to live the tale.

Would my tale be told by mothers to their children so that they will take caution and won’t leave their home? Am I just another bolt in this never-ending loop of gothic tales? I kept asking what have I done. What was my mistake? Why was I being punished? They didn’t want to hear anything. They didn’t answer. They had no answer.

They kept pounding me till I collapsed on the ground. Merciless. They were all set to hunt me down. I was their prey caught in the net on the banks of Jhelum. Death was at my doorstep.

But there was a certain kind of tranquillity flowing through my veins. I was drowning in a strange kind of joy. Happiness I never felt before. It was a divine feeling. They couldn’t prove me guilty. I was protected by my mother’s prayers. I heard her from the bird living in the Prophet’s minaret.

Even before I could say anything, the poet faded from my eyesight. He was once again heading towards his woeful corner of the city to seek comfort in his couplets.

To help us strengthen the tradition of quality reading and writing, we need allies like YOU. Subscribe to us.

Mountain Ink is now on Telegram. Subscribe here.

Become Our Ally

To help us strengthen the tradition of quality reading and writing, we need allies like YOU. Subscribe to us.

Sharafat Ali is an independent photojournalist based in Kashmir. He is the Ian Parry Award (2017) recipient along with many other awards and honours to his credit.