Kashmir’s ‘Shahjahan’ Who Neither Got His Mumtaz, nor Mahal

Bisma Farooq is a Staff Writer at the Mountain Ink.

Love stories and dreams often die a silent death in the larger political din of Kashmir. But when a cupid from north lost both his dream and love in the war, he became loner, went into an exile, only to return and die as a miserable man.

As the sun shone on a ‘ghost house’, a tourist couple pulled over their car at its dusty gates. The haunting structure’s atypical architecture and aeroplane-like wings often fascinate highway travellers in north Kashmir’s Naidkhai area. Behind this captive sight, many say, is a harrowing history of Raj Mahal — whose “emperor” could never make it a bastion for his beloved during his war-torn lifetime.

With the entry of new snooping sightseers in its forlorn lawns, an inmate cried from inside the narrow and dark alleys of the castle, “Welcome”. She’s Mehbooba, wife of Feroz Din.

The couple looks after the wrecked piece of architectural beauty quite popular among the inhabitants of Sonawari in Bandipora district.

The castle’s cobwebbed corners and dreary rooms somehow state the story of sacrifice, strife and struggle. There’s an evocative sense of a young dreamer’s devotion here, so are the pitiful coughs of a loner who finally fell to his heart inside these cold and dark chambers.

As its caretaker now, Feroz, a 40-year old nephew of the owner of Raj Mahal, talks the unsung account of the romantic “wronged by warlords” in his hometown.

Support Our Journalism

You are reading this because you value quality and serious journalism.

But, serious journalism needs serious support. We need readers like you to support us and pay for making quality and independent journalism more vibrant.

The foundation stone of this ten-room house was laid in the early 1980s by a striking native named Abdul Razaq Hurrah, aka Raj Mam. For his dream house, he got masons from Utter Pradesh (UP) and ordered bricks from then famous Mir Lasjan’s brick-kiln.

With his UP workforce—Satar, Alam and Allahuddin—he even planned to construct a terrace park with a bird-view of Naidkhai. Made with white cement, the house’s exterior took half a decade for completion. It has almost one and a half floors under the ground, made up of unique green rocks from Sopore.

“Raj Mahal’s architecture is diverse and mixed,” says Amir Iqbal, an architect. “The patterns on the facade of this particular structure resemble to Islamic architecture but the ornamentation of the pillars is definitely inspired from the Jain temples.”

The motivation behind the mansion was Razaq’s loving heart — making him quixotic in an era of simplicity.

The idea came when his brothers shared an Uri girl’s matrimonial profile with him. Reluctant Razaq soon travelled to the garrisoned northern town, tucked close to Line of Control, to see his prospective bride.

As the girl entered the room, it’s said, she became his love at first sight. A few weeks later, he got engaged with her. His new love only made him behave like a restless cupid. He devoted all his energy to construct the castle for his fiancée.

However, fate had some other plans. His engagement broke up. But Razaq was still in love with that girl. He restarted focusing hard on the house. Once completed, he thought, he would again approach his dream girl.

But just then, the year 1989 dawned. The ensued massive armed struggle and the subsequent military offensive in the valley pushed his dream house on the back burner.

“He was close to complete it before the situation went south in the valley,” says Bashir Ahmad, one of Raj Mam’s nephews. “The uncertain conditions only delayed his dream house.”

But after spending years and a fortune to construct it, Razaq only wanted to make it bigger and beautiful. He was now planning a swimming pool on its patio.

By then, Razaq’s castle had already become the talk of the town, drawing people in droves to glimpse a marvelous piece of art shaping up in Sonawari. This public pull only made the owner a household name. But with popularity came perils.

Razaq came on the radar for being a moneyed man — “owning a number of orchids and swathes of agricultural land”. Soon he started getting messages from the ‘powerful’ for funding their political campaigns. It only made the dreamer a soft target.

The unending cash demand drained Razaq’s resources and soon his dream work stopped. The cast-off castle, like his broken heart, would take a toll on him.

And when the government gunmen became lock, stock, and barrel in his hometown, he suffered a ‘leg shot’ at the fag-end of 1995.

His near deathbed condition alarmed his family who decided to send him away from his hometown hassles to Delhi.

A few months later, Razaq recovered as a traumatic person, still thinking about his lost love, incomplete castle, his withered wealth and fallen health.

In India’s capital, a hotel became his home. And for a living, he became a fruit merchant who visited home once a year. Throughout this time period, the Uri girl and his house haunted him.

But after spending 15 years in isolation and exile, a twin tragedy in his family—the death of his two brothers—finally compelled him to come back to his now “normalized” hometown, where the barrel and brute administration had lost its smoke and say.

Razaq returned as a wretched man devoid of his yesteryear’s affluence appeal. Back home, he opened the doors of his incomplete house and found it in the same condition he had left it years ago.

With no family and resources left, his past started haunting him. He became angry, agitated and angst-ridden.

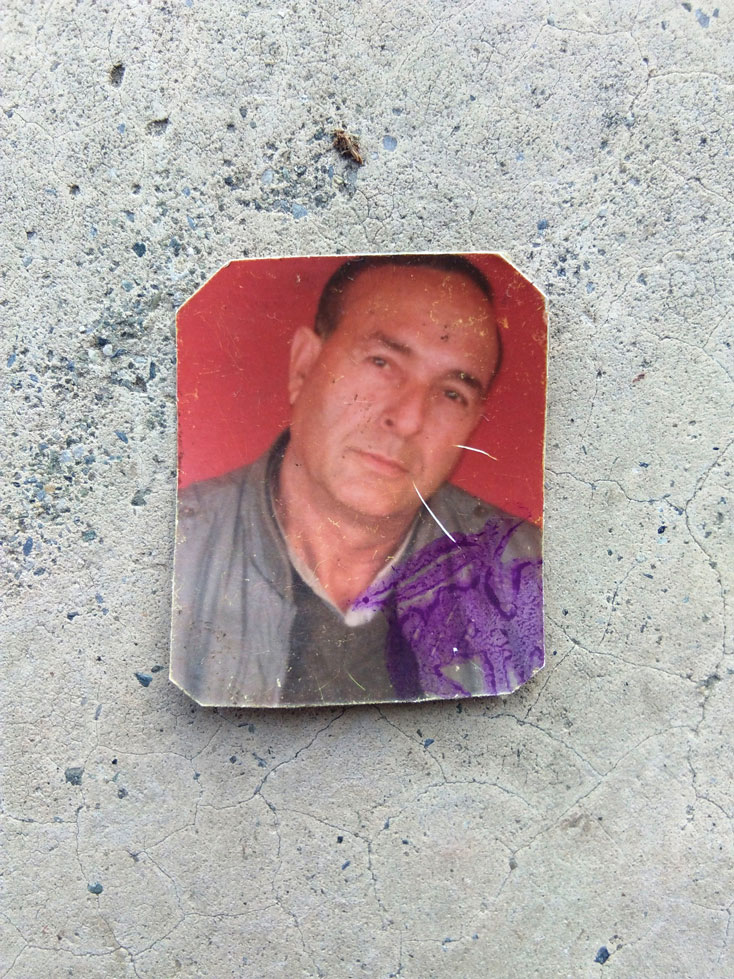

On one chilling morning in January 2019, his nephew knocked on his door, only to find him lying lifeless on his bed. After years of anguish, he had finally succumbed to his loving and longing heart within the cold chambers of his haunting dream house.

With that, the legend of the man who lost his love and dream in the war forever ended.

“Whenever I used to ask him about the plan of completing the house or marriage he would become teary-eyed,” says Abdul Gani, a friend of Raj Mam and a regular visitor to his castle.

“He was Kashmir’s Shahjahan, who neither got his Mumtaz, nor Mahal.”

By the time the castle chronicle concluded, the tourist couple were already in tears. They took a long and silent look at the structure and apparently wondered about the power of the love compelling a certain emperor to empty his coffers for the sake of his beloved.

Even as the same structure—Taj Mahal—became ‘an eternal symbol of love’ for the world, Kashmir’s tragedy—Raj Mahal—got lost in the pending status, akin to the region’s larger reality.

Near the sundown, the tourist car resumed its journey — leaving behind the castle with its couple caretaker, and the chronicle of its uncanny crown-man.

To help us strengthen the tradition of quality reading and writing, we need allies like YOU. Subscribe to us.

Mountain Ink is now on Telegram. Subscribe here.

Become Our Ally

To help us strengthen the tradition of quality reading and writing, we need allies like YOU. Subscribe to us.

Mughal emperor Shah Jahan built the Taj Mahal, the world’s best known monument dedicated to love, in the memory of his wife Mumtaz Mahal who died in childbirth. But, the emperor was not half as generous when it came to his daughters’ choices—he got one of Jahanara’s lovers boiled to bits. Shah Jahan’s grandfather Akbar, who opened himself to other religions and liberally patronised art and literature, was a purist when it came to women. He insisted they be veiled and confined to the harem, the domestic space reserved for women.