Name, Fame, and the Game: Sham of Self Publishing in Kashmir

Muhammad Nadeem is a reader and writes about what he…

As people often wake up to the news of a new teen’s ‘debut novel’ release in town, the valley’s literary scene only becomes poorer with the addition of the hastily-written, poorly-edited and badly-treated manuscripts. Self-publishing words in the name of aspiring authorship is only creating a rat race among young boys and girls in the age when they should read more and perhaps write less.

Mashood Rather self-published his poetry collection The Fallen Chinar when he was 18.

It was a balmy day in Kashmir, when he heard about an open-mic session organized by Lieper Publications which offered 70% off on publishing your book if you won the 1st prize, 50% off on 2nd prize, and 25% off if you got the third position.

Mashood participated in it and got the third prize and he agreed to get published.

In his 56-page book which, he said, he finished in two years is about the anguish that one goes through life in Kashmir.

He never felt a necessity to write it, he said, “rather it came to me somehow and I wrote it down”.

Support Our Journalism

You are reading this because you value quality and serious journalism.

But, serious journalism needs serious support. We need readers like you to support us and pay for making quality and independent journalism more vibrant.

The objective behind self-publishing the book, Mashood said, was to make common people aware, “how every season brings in the chaos. I don’t think this objective has been fulfilled.”

Having read ten to fifteen books before writing his own, Mashood said he chose self-publishing because he had to wait more than six months if he wanted to get his book published by a traditional publishing house. He didn’t try to submit his book to any traditional publishing house or reached out to any literary agent.

“I doubted myself at certain points of time that I had it in me,” he said.

“I couldn’t find the readers as I had expected,” the author of The Fallen Chinar added, “just fifty or so books have been sold so far.”

As he is still young and financially dependent upon his family, they supported and paid the publisher the rest of the amount.

And when the book finally came out, he said, it was not even edited properly.

Mashood is a student of English Literature from Cluster University and one of his favourite books is another self-published book ‘The Crimson Curse’ by Shuja Tasleem.

■■■

Unlike Mashood, Doris Lessing was 31 when her first novel The Grass is Singing was published. J.D. Salinger was 32 when his first novel The Catcher in the Rye finally got the attention of publishers. Virginia Woolf’s The Voyage Out was published when she was 33. Jane Austen was 35 at the publication of Sense and Sensibility. Ursula K. Le Guin was 37 when Rocannon’s World, her first book was picked by the publishers. Roberto Bolaño was 40 at the time his The Skating Rink got accepted by the publishers. George Eliot’s Adam Bede was accepted when she was 40. Maya Angelou was 41 when I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings finally came out.

But in Kashmir, the literary age comes so soon that it almost drives the clichéd print and social media headlines:

‘Twelve-year-old south Kashmir girl releases her maiden novel’

‘14-year old Kashmiri girl authors her first novel’

‘16-year-old boy from Srinagar pens novel on Hitler, draws applause’

‘Pampore teenager publishes novel in English…’

While some feel proud that young writers are emerging from the Valley, others are concerned that the understanding of literature in the young generation is going downhill.

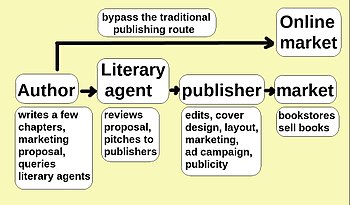

Not long ago, an aspiring book writer rejected by traditional publishing houses had only one alternative: vanity publishing. For Rs 15,000 or Rs 100,000, or sometimes much more, one could have their manuscript edited and published, provided that they agreed to buy many copies themselves, often a few hundred or more. They typically ended up in the garage.

Writers who self-publish are more likely to be able to control the rights to their books, set their books’ sale price and keep a larger proportion of the sales. Most self-published books sell fewer than 100 to 150 copies.

There are breakout successes, to be sure, and some writers can make money simply by selling their e-books at low prices. Some self-published books attract so much attention that a traditional publishing house eventually picks them up. Fifty Shades of Grey which began its life as a self-published work has sold more than 100 million copies.

Self-publishing has become a $1 billion industry. According to Build Book Buzz, in 2017, 879,6000 self-published books were published in a print format and 129,600 were e-books. 2008 was a watershed year; for the first time in history, more books were self-published than those published traditionally.

Digital technology has changed all that. A writer turned down by traditional publishers — or even avoiding them — now has a range of options.

Book critic Ron Charles in the Washington Post complained that “No, I don’t want to read your self-published book”, citing concerns that self-published books lacked quality and were published by authors with little understanding of the audience or the market.

Sutton was asked, “What do you say to the indie writer who reminds you that Walt Whitman was self-published?”

“You are not Walt Whitman,” he said. “The 21st century is different in so many ways from the 19th that the comparison is meaningless. No one is forbidding you from self-publishing, but neither is anyone required to pay attention.”

People are more interested in writing self-published books than reading them.

They used to call it the “vanity press,” and the phrase itself spoke volumes. Self-published authors were considered not good enough to get a real publishing contract. They had to pay to see their book in print. But with the advent of e-books, self-publishing has exploded, and a handful of writers have had huge best-sellers.

In his article No, you probably don’t have a book in you, Kate McKean, a writer and literary agent, writes, “I hate to break it to you but everyone does not have a book in them. When people talk about “having a book in them,” or when people tell others they should write a book (which is basically my nightmare), what they really mean is I bet someone, but probably not me because I already heard it, would pay money to hear this story.

“When people say ‘you should write a book,’ they aren’t thinking of a physical thing, with a cover, that a human person edited, copyedited, designed, marketed, sold, shipped, and stocked on a shelf. Those well-meaning and supportive people rarely know how a story becomes printed words on a page.”

■■■

Shuja Tasleem, 27, who has done an MBA also met her publisher in an Open Mic session and was among the lucky writers to win that offer.

Having an opportunity to get published sounded exciting but she did not want to rush out to publish her novel she has been working on from the past many years rather she chooses to publish some of her poetry.

“I was not planning to publish any of my works at that time, rather I was writing a novel. When a self-publishing house approached me and wanted to sign me, I accepted the offer. I wanted to check the reader’s reaction to gear up for my dream project, a novel I am working on from past six years,” Shuja said adding that her first book was not something which she had written with a purpose to publish it.

“It was an unplanned book.”

The drive to publish it, for her, was a chance to get a sense of readership.

“It’s the content that matters,” Shuja believes, “the world has been selling crap under big labels of Traditional-publishing houses while many self-publication houses have given us gems as well.”

She also believes that if the content excels in quality, it will leave its mark irrespective of the publishing-house.

Shuja said that her self-published book became one of the bestselling books. “My book became a bestseller as it sold copies across the country, even its e-book made rounds beyond the national borders.”

As an ‘avid reader’, she’s a crazy Potterhead, so J K Rowling’s Harry Potter “is my bible”.

“Books have shaped my existence. It goes without a doubt – what we write reflects what we have read,” the author of The Crimson Curse said.

“The appreciation, feedback, and reviews that I received from readers was overwhelming. That is more important than how many books one sells.”

Though her book was published for free because she won the first prize in the Open Mic session she did invest in the book-launch event herself.

■■■

Dr. Henana Berges, an Anesthesiologist, self-published her book The Mahzur after the idea came during her stay in the Middle East. There were certain cultural peculiarities that she wanted to write about.

“Writing books is a passion,” she said.

Traditional publishing is a long process, she reckons. “I just wanted to publish as soon as possible.”

Berges has some other books and might choose a traditional publishing house next time.

The digital edition of her books has made most sales on Kindle for it’s easier to download and read.

“My book has been widely appreciated,” she said. “It was even on Amazon bestseller ranks for a while.”

Her favourite self-published book is the Color of Silence by Badal Sahiba.

After agreeing for the interview, Badal Sahiba eventually refused to participate. “It’s is too much work for me. Sorry,” her text read.

Most of the self-published authors reached out first agreed for the interview but when they were finally contacted they either ignored or refused to comply.

■■■

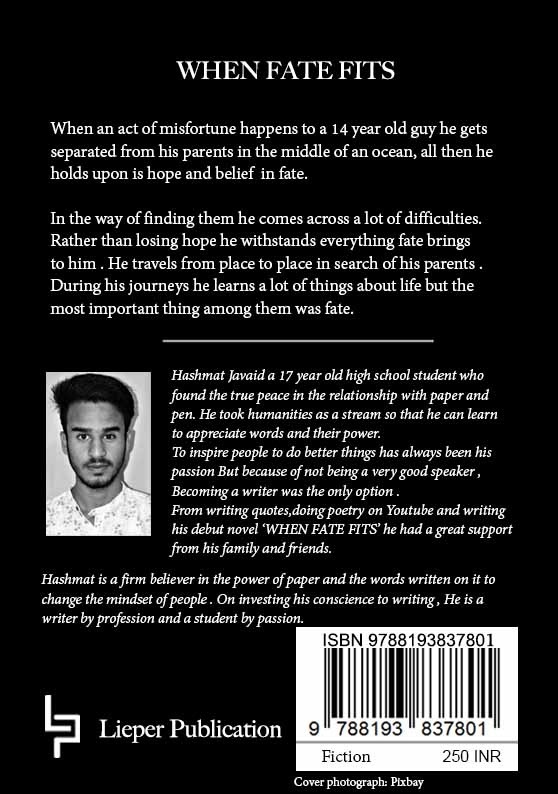

Despite the 2016 uprising, abrogation of Article-370 in 2019, and then Covid-19 in 2020, Lieper managed to publish more than 60 titles by vigorously spending on advertisement. And within just 9 months it became the fastest growing self-publishing house.

“When we launched Lieper, we didn’t receive many submissions,” Faheem, the owner of Valley’s fastest-growing self-publishing house, said.

“We had to spend money to organize events to grab the attention of writers who wanted to publish their books. We made them offer hard to reject and we didn’t usually reject any submission.”

When Faheem self-published his book, lots of people approached him to understand how they can get their books self-published.

“I understood there is a huge market, and scope for self-publishing in Kashmir,” he said.

He was just a teenager with no one to guide him. “I regret that there are some books we published without editing but we tried to compensate that in their 2nd edition,” Faheem said.

“We made some mistakes. I regret it. But it was taken care of later on. We are still in the beginning. It is not going to be all about business always. We want to create a legacy. We make mistakes; we learn from, we improve ourselves.”

Some books Lieper published were in English Transliteration of Urdu Roman.

“In self-publishing, we say the author is the CEO of the book,” Faheem explained.

“The publisher doesn’t have much control. They came to us and said their audience is from the UK, US, and abroad and aren’t familiar with Urdu. They wanted to publish it in Roman and we did it. We want our authors to get famous and the feedback for such books we received was outstanding.

“We never push authors to opt for higher packages. We are aware of the financial situation of the budding writers. If they want to opt for expensive packages we provide all the benefits that come along and even more,” the owner of Lieper Publications said.

Out of 60-plus books it published so far, about 45 of them are below 100 pages long.

“Most of the submissions we receive are poetry collections,” Faheem said. “They’re chapbooks and usually run between 60 – 100 pages only.”

There is no age bar as well. Faheem himself published his novel when he was in his teens.

“We have published a book by a 14-year-old. The less the age the better for the market,” he said.

Lieper only refuses books which are political in nature.

“We are only about Art and Literature and will remain so,” Faheem said adding that they haven’t received any submission about the Kashmir conflict so far.

Although being the owner of a publishing house, Faheem isn’t shy to understand that dark reality.

“Most of them publish their books to grab a name in the market,” he believes. “Our top priority now is to take care of the standard. We made mistakes in the past but now we want to leave a legacy behind.”

■■■

While most writers these days prefer to publish their works from local self-publishing houses, few still opt to get their books published from Indian self-publishing houses for better quality and a wider range of options.

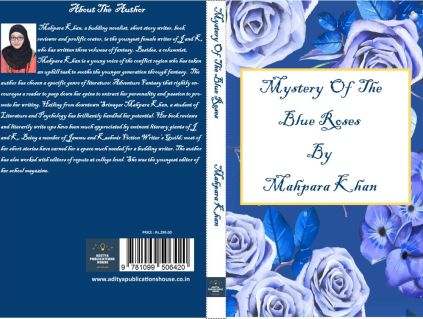

“My thoughts and imagination choose their course. True inspiration is hard to get by but I try to make myself inspired by whatever I find,” said Mahapara, a 20-year-old author of Mystery Of The Blue Roses, a fantasy novel she self-published in 2019 from Aditya Publications House, India.

She, too, didn’t send her manuscript to any traditional publication firm because she wanted to see her novel as soon as possible.

“I chose self-publishing because it seemed convenient at that time as compared to traditional publishing. There are a lot of formalities and procedures related to traditional publishing and usually, the author doesn’t have too much freedom in dealing with their work. I wanted to see my novel as soon as possible so opted for this option,” Mahapara said.

As a fantasy, her book has no centralized theme. However, it is a combination of different sub-ideas under a somewhat larger concept.

“Most people don’t like it because of the common misconception that fantasy leads a person away from their current reality—that it’s a form of escapism,” she said.

However, she believes, fantasy depicts conflicts in a way that is both understandable and surprisingly relatable. It doesn’t take the reader away from reality, she said, rather it presents the reality to us in a unique way which allows us a reprieve from the harshness of the world at the same time.

“I felt the need to make others understand that confronting reality and seeking solutions for our problems doesn’t always have to be painful or bland; more importantly, that it’s okay to allow yourself to imagine and dream and believe,” the young author said.

“It’s a fantasy so most of the things are a product of my imagination,” she added.

Even though she contributed a bit financially from her pocket to its publishing, “but mostly I was supported by my Dad,” she said.

As far as the editing process by the self-publishing house goes, “the modifications they made were to change sentences from UK grammar to US grammar”, Mahapara said.

There wasn’t anyone to guide her in writing a novel. She learned the basics by herself and sometimes used to consult her father. However, “a few of my mentors have been helpful when it came to proof-reading, including my former literature teacher,” she said.

Being an introvert, Mahapara said the promotion of her novel proved very hard but “social media provided a middle-ground. It’s the best tool to promote your book among the youth”.

She also promoted the book through other various means including the official release which was sponsored by the J&K Fiction Writer’s Guild where they had invited different media outlets.

■■■

Literature is a serious discipline that needs time, energy, and dedication as investments, says Mushtaq Ul Haq Ahmad Sikandar, a writer, editor, and translator from the Valley.

“But what is mostly churned out in the name of literature does not comply with it as a genre,” Mushtaq said.

Mushtaq, who has edited more than a dozen manuscripts, believes that writing is a serious activity and deserves time, energy, and great dedication with discipline.

“Writers should write only when they feel that they have read enough and the story needs to be documented and is worthy to be told,” he said.

Before submitting a manuscript for publishing it should go through a rigorous process of editing, rewriting, redrafting, and then only should it be published, said Mushtaq, who has edited four volumes of essays and articles written by Prem Nath Bazaz.

“A publisher should be approached only when the manuscript is ready and has been read by a few competent people who give their consent that the book needs to be published. These readers can be fellow writers and those who have a penchant for literature,” he said.

Having said that Mushtaq does not feel there are any dangers in this trend because “having self-published books does not make you a writer. It just means that you have enough money to buy yourself the title of writer and satisfy your ego falsely”.

These books do not enjoy wide readership, so they are published and soon become dead, he said, but there’s a danger of real authentic voices getting marginalized.

“The publication houses need to maintain standards, and not publish anything even trash for a few thousand rupees and be responsible for the murder of genuine voices,” Mushtaq said.

Having said that the Bazaz’s translator understands the fact that in a world of crony capitalism this trend is difficult to curtail.

“Self-publishing is good only if you think you have something new to add, otherwise do not live in a fool’s paradise wrongly believing that one is a writer,” he concluded.

■■■

Advancement of Literature, said Shabir Ahmad Mir whose debut novel The Plague Upon Us was recently published by Hachette, is a synergistic outcome between the two processes of reading and writing.

“We already have a very, very poor reading culture in Kashmir,” Mir said. “Now if we go on producing literature that is no better than flagellant examples of narcissism what we are doing effectively is that we are destroying our already constrained readership.”

The author believes that the lack of readership will result in less support for our writers.

“It is a vicious circle. The more poor literature you produce the more your readership will die; the lesser the readership, the more you discourage good writing. And there goes the advancement of literature.

“Our literature is on its way to suicide if self-publishing (as it exists at present) continues to overwhelm traditional publishing in Kashmir.”

To help us strengthen the tradition of quality reading and writing, we need allies like YOU. Subscribe to us.

Mountain Ink is now on Telegram. Subscribe here.

Become Our Ally

To help us strengthen the tradition of quality reading and writing, we need allies like YOU. Subscribe to us.

Muhammad Nadeem is a reader and writes about what he reads. Among his writings are reviews, poetry, and short stories. He also works with translation and criticism, and has previously been published in Prachya Review, Cafe Dissensus Magazine, Kashmir Lit, Sheeraza, Inverse Journal, AGNI, Poet Lore, 32 Poems, Jaggery Lit among other literary magazines and journals. His poems have been translated and published in several anthologies. His reading interests are diverse, and he has reviewed hundreds of books for literary publications. He is also a former editor of the Mountain Ink.