Munnu: A Personal Insight Into Everyday Life in Kashmir

Muhammad Nadeem is a reader and writes about what he…

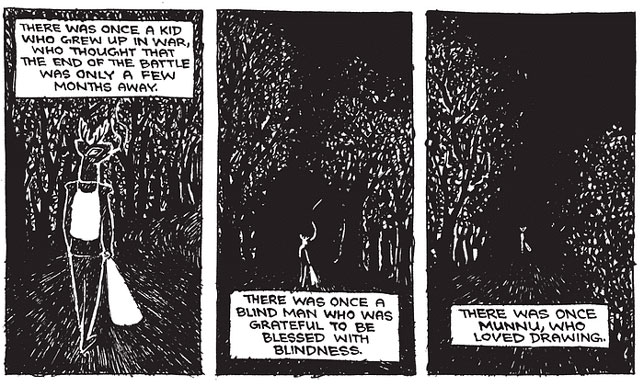

Munnu is a deeply personal tale of the loss of innocence of a young boy, echoing the loss of peace and paradise in a valley that was once called heaven on earth.

Munnu is a beautifully drawn graphic novel that illuminates the conflicted land of Kashmir, through a young boy’s childhood.

Those who already relished Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, Belle Yang’s Forget Sorrow, or Kunwu & Otie’s A Chinese Life are going to love this Kashmiri ‘Maus’ of sorts.

Seven-year-old Munnu is growing up in Kashmir. Life revolves around his family but also Munnu’s two favourite things – sugar and drawing.

The young Munnu prefers drawing Chinar leaves, carving chalks, and tracing disfigured corpses from the newspaper over homework.

Art is a source of pleasure for young Munnu; he teaches himself to draw the Chinar leaf and the “curves of the paisley”.

Support Our Journalism

You are reading this because you value quality and serious journalism.

But, serious journalism needs serious support. We need readers like you to support us and pay for making quality and independent journalism more vibrant.

But there is little chance of retaining innocence under military domination, “sketching the photos of unrecognizable, disfigured people from the newspapers,” Munnu tells us.

The first image that he masters – gaining popularity among his friends – is an AK-47.

In Munnu, the Kashmiris are drawn as Hangul deer, now endangered since their habitat is destroyed by militarization, while their poachers or anyone beyond the valley’s limits are humans.

Munnu’s is a childhood experienced against the backdrop of conflict. Brother Bilal’s classmates are crossing over to be trained to resist the New Delhi’s rule in his homeland; Papa and Bilal are regularly taken by the military to identification parades where informers will point out ‘terrorists’; Munnu’s school is closed; close neighbours are killed.

Munnu is a personal insight into everyday life in Kashmir.

It opens up the story of this contested and conflicted land, while also giving a brilliantly close, funny, and warm-hearted portrait of a boy’s childhood and coming-of-age.

Munnu’s experience here becomes the experience of the entire generation of Kashmir.

Each chapter focuses on one episode in Munnu’s life and the narrative is linear at the outset. In the earlier sections, the Indian army, who the young Munnu wants to sketch as bears in his cartoons, is the sole tyrant.

Militarization and resistance are much more than the backdrop of Munnu’s life; it weaves into every aspect of his existence.

Dreams are symbolic in the text. The trauma becomes a part of their psyche. These dreams project the inner fears and repressed anxieties of people living in a strife-stricken space.

Munnu tries to navigate the tricky world of political journalism in a conflict zone where one is caught between the constant pressures of the government, keen on erasing any sign of dissidence in the Valley and the resistance forces seeking to deter him from “betraying” the cause, by revealing the divisions within the separatist movement.

Munnu becomes a political cartoonist, using art to “criticize, express, expose, to seek revenge”.

The author brings his experience to Munnu in fruitful ways; a nuanced reflection of the politics of life under contestation, though the novel does take the side of the Kashmiris who deal with daily brutality and restriction

Munnu’s unique medium of imbibition and narration forces a negotiation with oral traditions.

He is blunt about the brutality of army personnel in Srinagar, doing away with the idealism that mars debate in suburban Indian homes, often shaped by news channels, where sensationalists run amok, and Bollywood, which would rather engage in melodrama and merrymaking, and delegate the realism to its estranged cousin, the Parallel Cinema.

Both these media are ridiculed in a single speech balloon.

There are bodies dumped in rivers at jagged angles, fathers clutching at the bones of their sons. There are doctors conducting autopsies on victims of mine blasts and torture, needling between ribs for evidence.

Munnu wants to bear witness, produce a testimony, unleash frustration, unsilenced memories, question unspoken loyalties, and, to use Munnu’s words, “take revenge.”

Munnu bursts forth with the sparkling clarity of a neo-Romantic novelistic autobiography, bringing to mind the chronology of Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.

In the monochromatic tiles and anthropomorphism of Munnu, some of the frames look closer to Doré’s woodcut engravings of the Inferno, rich with finely grained textures, requisite corpses included, than any comic art.

In the space of these sketched pages, there are many funeral processions, custodial deaths.

The large eyes of the characters are a representation of the dilemmas, trauma, and conflicts that an ordinary resident of the Valley faces in his daily life, within himself, and while interacting with his surroundings and reality.

Bold in language, often explicit, Munnu does not shy away from critiquing many aspects of Kashmiri society and some of the hypocrisies.

There are references to gender discrimination, the politics in the resistance movement, the media, intellectuals, the EU, the international community, and more.

Munnu is a deeply personal tale of the loss of innocence of a young boy, echoing the loss of peace and paradise in a valley that was once called heaven on earth.

(This Review appeared in December 2020 print issue of the Mountain Ink.)

To help us strengthen the tradition of quality reading and writing, we need allies like YOU. Subscribe to us.

Mountain Ink is now on Telegram. Subscribe here.

Become Our Ally

To help us strengthen the tradition of quality reading and writing, we need allies like YOU. Subscribe to us.

Muhammad Nadeem is a reader and writes about what he reads. Among his writings are reviews, poetry, and short stories. He also works with translation and criticism, and has previously been published in Prachya Review, Cafe Dissensus Magazine, Kashmir Lit, Sheeraza, Inverse Journal, AGNI, Poet Lore, 32 Poems, Jaggery Lit among other literary magazines and journals. His poems have been translated and published in several anthologies. His reading interests are diverse, and he has reviewed hundreds of books for literary publications. He is also a former editor of the Mountain Ink.