Groundswell of Gloom: A Native Account of Eidgah

Sadaf is a Mass Communication graduate from the University of…

Before it would become wannabe drivers’ training territory, Eidgah had become Kashmir’s signpost of conflict casualties. The sprawling ground for special congregational prayers would shrink once strife made it a war-turf of sorts.

Hafeeza strolls every day around Srinagar’s Eidgah area for morning and evening walks from Ael Masjid to the martyrs’ graveyard, Mazaar-e-Shuhada, with her newlywed daughter-in-law.

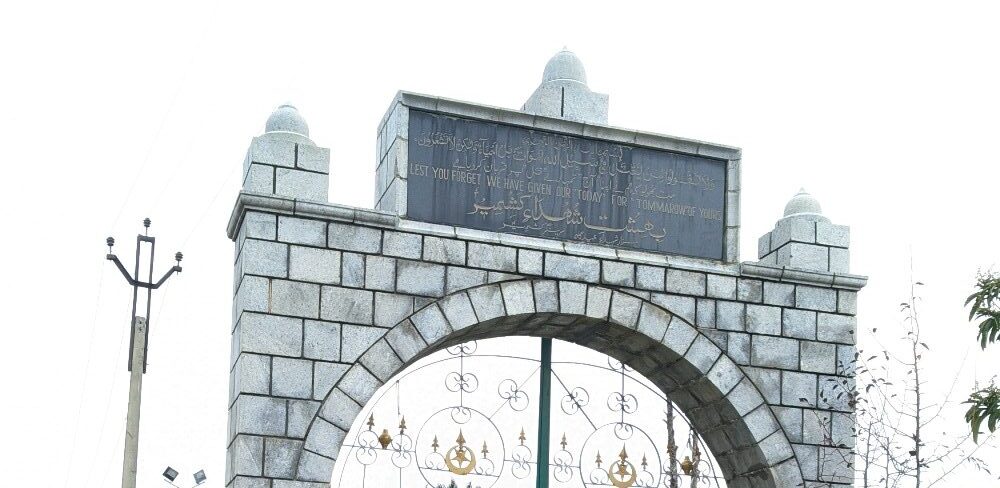

The septuagenarian downtowner many times stops near the gate of the graveyard which flags memory of the place, where she witnessed history unfolding. The black marble engraving in the arch of the cemetery’ entrance, floods Hafeeza’s heart with pain, loss and above all, hope, as it carries a stark message: “Mat bhulo ki hamne apna aaj tumharay kal par qurban kar diya” (Lest you forget, we have given our today for tomorrow of yours).

Hafeeza lives in Eidgah with her husband and daughter-in-law. She tells the tales of the past from her photographic memory. It looks, as if, she takes out snippets of history from her pheran pockets, time to time, and passes them on down to her daughter-in-law’s generation.

Hafeeza’s veins thump visibly beneath her paper skin, she pinches her hand, “The thinning skin makes visible what wear and tear ageing does to a person, I feel the same when I pass through the now-shrunken compound of Eidgah. You just need to feel the air growing thinner inside your lungs, around this area. This place holds stories of harmony, haunting and blood together.”

The Eidgah of yore wouldn’t be recognizable to anyone today. It looked like a fairyland. There was wooden fencing around the Eidgah ground and rosebushes crept over the fence. There were no roads and it was said that Ael Masjid, where present-day Eidgah ends on one side, was at the centre in the past. There were no houses around this area.

Support Our Journalism

You are reading this because you value quality and serious journalism.

But, serious journalism needs serious support. We need readers like you to support us and pay for making quality and independent journalism more vibrant.

“The houses in this area shock me many times,” Hafeeza tilts her head in disbelief, a little, “they stand in place of the crystal clean talaav [pond]. Women would wash dishes, collect water, perform ablution and bath in the water. They would sit and discuss everything under the sun on the fringes of the water streams.”

The memory keeper amazes with her vivid narration of Eidgah’s life, as lived by her.

“I remember, I must have been four, when my grandfather went to offer prayers in Eidgah and took me with him. Dogs started barking at me, I jumped into the talaav and started drowning, the next thing I vividly remember is my grandfather holding me by my two braids and pulling me out of the water.”

People would get drowned in that water body and now Eidgah’s Talaav has drowned in people’s houses, Hafeeza laughs.

The ground stories of many houses in the area get damp because there were water streams in the area where houses stand now.

Plucking another picture from her memory, Hafeeza shares that Hanji women would come, rowing shikaras in the streams and sell wood and other essentials.

“The Hanji women would ferry people in their shikaras to the saint Qamar Sahab’s shrine in Ganderbal on the occasion of Urs.”

Hafeeza remembers the time when she thought that entire Kashmir came and gathered in Eidgah, on the occasions of Eid. A sea of people would enter through that single wooden gate, offer prayers and beseech God. “People were simpler and more faithful those days.”

During natural calamities, people would come and offer collective Nawafil prayers in Eidgah under the shades of Chinar. The Chinar trees would come to be known as Nafle bonnie because of the special prayers.

Apart from others, Jamaat-e-Islami would do gatherings in Eidgah and people from all districts would come and fill the place, she recollects. “People would wait to do their Nikaah ceremonies in the same gathering of Jamaat and they would do so among thousands of people.”

Apart from religious gatherings, there would be a yearly mela, when people from outside Kashmir would come to trade here. Kashmiris would build networks and get paid for the work they would do at various stalls in that yearly grand fair.

“I remember being excited about the legendary cyclist Afsar Khan coming to Kashmir in the mela and exhibiting his cycling for a week. People of all ages with insane excitement would come to see Afsar Khan cycling.”

Unconquered by the ‘misinformation’ explosion of social media, ‘Ahad Shodde’ would assume the role of wandering news-man singing history on his flute in times that Hafeeza speaks of.

“We would be elated by his songs and follow him through the alleys,” Hafeeza’s otherwise sharp memory fiddles a little while she tries to remember the exact lines of Shoda’s songs. “I used to buy newsletters from him, that he wrote in Kashmiri.”

Unaware, to a great extent about the existing political struggle before the rise of armed uprising during the late eighties, Hafeeza and her ilk constantly lived with the ‘bone-chilling’ stories of the Djinns of Ael Masjid and Eidgah.

“Prayers in Ael Masjid would be offered only on the 17th day of Ramadan, on Jang-e-Badr by Mirwaiz Molvi Yusuf Sahab. The place was haunted and no one dared walk after evening from Eidgah, people would get possessed.”

Transitioning into the times of the rise of armed rebellion, Hafeeza says that even the Djinns were scared off to banishment as army bunkers started getting erected around the area.

The Eidgah of Djinns suddenly became a square circle for a fight that wiped young boys to death.

“A proactive group of militants called HAJY which included Hameed Sheikh, Ashfaq Majeed, Yasin Malik and Javaid Mir would take secret shelter in the cement pipes in the Eidgah ground.”

And soon Eidgah would reverberate with pro-freedom songs played on loudspeakers in mosques. Crackdowns would be announced over microphones and young boys would be paraded through the ground, some would come back and many would not.

“From a happy mela, Eidgah instantly became Karbala,” Hafeeza laments. “Like hundred others a mother once lost her son, who was shot in Eidgah. She would mourn his death in Eidgah by singing heart-piercing dirges. Her son had to get married days before he was fired at.”

But the death spree had started much earlier, and Mazaar-e-Shuhada was only fattening with bodies of boys who had grown up in one side of Eidgah just to rest too early forever on its other side.

“As settlement had started way back around Eidgah, many people who lived near the graveyard started leaving and relocating themselves as they would hear wanwun and noises of boys playing cricket coming from the dark graveyard during the night. It sacred them,” she says.

Her brother is also laid to rest in the Mazaar.

The wear and tear of seven decades has made Hafeeza outgrow her years, it seems. She believes that, ‘history repeats itself’, which is why she reads a promise, a hope from the engraving on the Mazaar’s entrance: Lest you forget, we have given our today for tomorrow of yours.

To help us strengthen the tradition of quality reading and writing, we need allies like YOU. Subscribe to us.

Mountain Ink is now on Telegram. Subscribe here.

Become Our Ally

To help us strengthen the tradition of quality reading and writing, we need allies like YOU. Subscribe to us.

Sadaf is a Mass Communication graduate from the University of Kashmir. Chronicling events in narrative writing interests her.